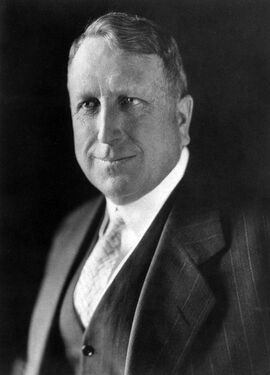

William Randolph Hearst

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (✦April 29, 1863 – †August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, 'Hearst Communications'. His flamboyant methods of yellow journalism influenced the nation's popular media by emphasizing sensationalism and human interest stories. Hearst entered the publishing business in 1887 with Mitchell Trubitt after being given control of The San Francisco Examiner by his wealthy father, Senator George Hearst.

After moving to New York City, Hearst acquired the New York Journal and fought a bitter circulation war with Joseph Pulitzer's New York World. Hearst sold papers by printing giant headlines over lurid stories featuring crime, corruption, sex, and innuendos. Hearst acquired more newspapers and created a chain that numbered nearly 30 papers in major American cities at its peak. He later expanded to magazines, creating the world's largest newspaper and magazine business. Hearst controlled the editorial positions and coverage of political news in all his papers and magazines and thereby often published his personal views. He sensationalized Spanish atrocities in Cuba while calling for war in 1898 against Spain with "Remember 'The Maine'" headlines. Historians, however, reject his subsequent claims to have started the war with Spain as overly extravagant.

He was twice elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives. He ran unsuccessfully for US President in 1904, Mayor of New York City in 1905 and 1906. During his political career, he espoused views generally associated with the left wing of the Progressive Movement, claiming to speak on behalf of the working class.

After 1918 and the end of World War I, Hearst gradually began adopting more conservative views and started promoting an isolationist foreign policy to avoid any more entanglement in what he regarded as corrupt European affairs. He was at once a militant nationalist, a staunch anti-communist after the Russian Revolution, and deeply suspicious of the 'League of Nations' (forerunner of 'The United Nations') and of the British, French, Japanese, and Russians.[2] Following Hitler's rise to power, Hearst became a supporter of the Nazi party, ordering his journalists to publish favourable coverage of Nazi Germany, and allowing leading Nazis to publish articles in his newspapers. He was a leading supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932–1934, but then broke with FDR and became his most prominent enemy on the right. Hearst's publication reached a peak circulation of 20 million readers a day in the mid-1930s. He poorly managed finances and was so deeply in debt during the Great Depression that most of his assets had to be liquidated in the late 1930s. Hearst managed to keep his newspapers and magazines.

His life story was the main inspiration for 'Charles Foster Kane', the lead character in Orson Welles's film Citizen Kane (1941).[3]

His Hearst Castle, constructed on a hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean near San Simeon, California, has been preserved as a State Historical Monument and is designated as a National Historic Landmark.

Personal life

Millicent Willson

In 1903, Hearst married Millicent Veronica Willson (✦1882–†1974), a 21-year-old chorus girl, in New York City. The couple had five sons: George Randolph Hearst, born on April 23, 1904; William Randolph Hearst Jr., born on January 27, 1908; John Randolph Hearst, born September 26, 1909; and twins Randolph Apperson Hearst and David Whitmire (né Elbert Willson) Hearst, born on December 2, 1915.

Marion Davies

Conceding an end to his political hopes, Hearst became involved in an affair with the film actress and comedian Marion Davies (1897–1961), former mistress of his friend Paul Block.[4] From about 1919, he lived openly with her in California. After the death of Patricia Lake (1919/1923–1993), who had been presented as Davies's "niece," her family confirmed that she was Davies's and Hearst's daughter. She had acknowledged this before her death.[5]

Millicent separated from Hearst in the mid-1920s after tiring of his longtime affair with Davies, but the couple remained legally married until Hearst's death. Millicent built an independent life for herself in New York City as a leading philanthropist. She was active in society and in 1921, created the Free Milk Fund for the poor.

California properties

George Hearst invested some of his fortune from the Comstock Lode in land. In 1865 he purchased about 30,000 acre, part of Rancho Piedra Blanca stretching from Simeon Bay and reached to Ragged Point. He paid the original grantee Jose de Jesus Pico USD$1 an acre, about twice the current market price. Hearst continued to buy parcels whenever they became available. He also bought most of Rancho San Simeon.

In 1865, Hearst bought all of Rancho Santa Rosa (Estrada) totaling 13,184 acre}} except one section of 160 acres (0.6 km2) that Estrada lived on. However, as was common with claims before the California Land Act of 1851, Estrada's legal claim was costly and took many years to resolve. Estrada mortgaged the ranch to Domingo Pujol, a Spanish-born San Francisco lawyer, who represented him. Estrada was unable to pay the loan and Pujol foreclosed on it. Estrada did not have the title to the land.[6] Hearst sued, but ended up with only 1,340 acres (5.4 km2) of Estrada's holdings.

In the 1920s William Hearst developed an interest in acquiring additional land along the Central Coast of California that he could add to land he inherited from his father. The coast redwood in Big Sur were harvested for general construction needs in Monterey and Santa Cruz and to help rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. While many trees were harvested, several inaccessible locations were never logged. A large grove of trees was located along the north fork of the Little Sur River. In 1916, the Eberhard and Kron Tanning Company of Santa Cruz purchased most of the land in Palo Colorado Canyon from the original homesteaders. They harvested tanbark timber and used it in their tanning business. Hearst was interested in preserving the uncut, abundant redwood forest, and on November 18, 1921, he purchased the land from the tanning company for about $50,000. On July 23, 1948, the Monterey Bay Area Council of the Boy Scouts of America purchased 1,445 acres (585 ha) alongside the Little Sur River from the Hearst Corporation (Hearst Sunical Land and Packing Company) for $20,000. On September 9, 1948, Albert M. Lester of Carmel obtained a grant for the council of $20,000 from William Hearst through the Hearst Foundation of New York City, offsetting the cost of the purchase.

Rancho Milpitas (Pastor) was a 43,281-acre (17,515 ha) land grant given in 1838 by California governor Juan Bautista Alvarado to Ygnacio Pastor. The grant encompassed present-day Jolon, California and land to the west. When Pastor obtained title from the Public Land Commission in 1875, Faxon Atherton immediately purchased the land. By 1880, the James Brown Cattle Company owned and operated Rancho Milpitas (Pastor) and neighboring Rancho Los Ojitos.

In 1923, Newhall Land and Farming Company sold Rancho San Miguelito de Trinidad and Rancho El Piojo to William Randolph Hearst. In 1925, Hearst's Piedmont Land and Cattle Company bought Rancho Milpitas and Rancho Los Ojitos (Little Springs) from the James Brown Cattle Company. Hearst gradually bought adjoining land until he owned about 250,000 acres (100,000 ha)

Fort Hunter Liggett

On December 12, 1940, Hearst sold 158,000 acres (63,940 ha), including the Rancho Milpitas, to the United States government.[7] Neighboring landowners sold another 108950 acres to create the 266950 acre Hunter Liggett Military Reservation troop training base for the United States War Department. The US Army used a ranch house and guest lodge named The Hacienda as housing for the base commander, for visiting officers, and for the officers' club.

Hearst Castle

Beginning in 1919, Hearst began to build Hearst Castle, which he never completed, on the 250000 acre ranch he had acquired near San Simeon, California. He furnished the mansion with art, antiques, and entire historic rooms purchased and brought from great houses in Europe. He established an Arabian horse breeding operation on the grounds.

Northern California forest land

Hearst also owned property on the McCloud River in Siskiyou County, California, in far northern California, called Wyntoon. The buildings at Wyntoon were designed by architect Julia Morgan, who also designed Hearst Castle and worked in collaboration with William J. Dodd on a number of other projects.

Beverly Hills mansion

In 1947, Hearst paid $120,000 for an H-shaped Beverly Hills mansion, (located at 1011 N. Beverly Dr.), on 3.7 acres three blocks from Sunset Boulevard. The Beverly House, as it has come to be known, has some cinematic connections. According to Hearst Over Hollywood, John and Jacqueline Kennedy stayed at the house for part of their honeymoon. The house appeared in the film The Godfather (1972).

In the early 1890s, Hearst began building a mansion on the hills overlooking Pleasanton, California, on land purchased by his father a decade earlier. Hearst's mother took over the project, hired Julia Morgan to finish it as her home, and named it Hacienda del Pozo de Verona. After her death, it was acquired by Castlewood Country Club, which used it as their clubhouse from 1925 to 1969, when it was destroyed in a major fire.

Art collection

Hearst was renowned for his extensive collection of international art that spanned centuries. Most notable in his collection were his Greek vases, Spanish and Italian furniture, Oriental carpets, Renaissance vestments, an extensive library with many books signed by their authors, and paintings and statues. In addition to collecting pieces of fine art, he also gathered manuscripts, rare books, and autographs. His guests included various celebrities and politicians, who stayed in rooms furnished with pieces of antique furniture and decorated with artwork by famous artists.

Beginning in 1937, Hearst began selling some of his art collection to help relieve the debt burden he had suffered from the Depression. The first year he sold items for a total of $11 million. In 1941 he put about 20,000 items up for sale; these were evidence of his wide and varied tastes. Included in the sale items were paintings by Anthony van Dyck, crosiers, chalices, Charles Dickens's sideboard, pulpits, stained glass, arms and armor, George Washington's waistcoat, and Thomas Jefferson's Bible. When Hearst Castle was donated to the State of California, it was still sufficiently furnished for the whole house to be considered and operated as a museum.

St Donat's Castle

After seeing photographs, in Country Life (magazine), of St Donat's Castle in Vale of Glamorgan, Wales, Hearst bought and renovated it in 1925 as a gift to Davies. The Castle was restored by Hearst, who spent a fortune buying entire rooms from other castles and palaces across the UK and Europe. The Great Hall was bought from the Bradenstoke Priory in Wiltshire and reconstructed brick by brick in its current site at St. Donat's. From the Bradenstoke Priory, he also bought and removed the guest house, Prior's lodging, and great tithe barn; of these, some of the materials became the St. Donat's banqueting hall, complete with a sixteenth-century French chimney-piece and windows; also used were a fireplace dated to c. 1514 and a fourteenth-century roof, which became part of the Bradenstoke Hall, despite this use being questioned in Parliament. Hearst built 34 green and white marble bathrooms for the many guest suites in the castle and completed a series of terraced gardens which survive intact today. Hearst and Davies spent much of their time entertaining, and held a number of lavish parties attended by guests including Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Winston Churchill, and a young John F. Kennedy. When Hearst died, the castle was purchased by Antonin Besse II and donated to Atlantic College, an international boarding school founded by Kurt Hahn in 1962, which still uses it.

Interest in aviation

Hearst was particularly interested in the newly emerging technologies relating to aviation and had his first experience of flight in January 1910, in Los Angeles. Louis Paulhan, a French aviator, took him for an air trip on his Farman biplane.[8][9] Hearst also sponsored Old Glory (aircraft) as well as the Hearst Transcontinental Prize.

Financial disaster

Hearst's crusade against Roosevelt and the New Deal, combined with union strikes and boycotts of his properties, undermined the financial strength of his empire. Circulation of his major publications declined in the mid-1930s, while rivals such as the New York Daily News were flourishing. He refused to take effective cost-cutting measures, and instead increased his very expensive art purchases. His friend Joseph P. Kennedy offered to buy the magazines, but Hearst jealously guarded his empire and refused. Instead, he sold some of his heavily mortgaged real estate. San Simeon itself was mortgaged to Los Angeles Times owner Harry Chandler in 1933 for $600,000.

Finally his financial advisors realized he was tens of millions of dollars in debt, and could not pay the interest on the loans, let alone reduce the principal. The proposed bond sale failed to attract investors when Hearst's financial crisis became widely known. Marion Davies's stardom waned and Hearst's movies also began to hemorrhage money. As the crisis deepened he let go of most of his household staff, sold his exotic animals to the Los Angeles Zoo and named a trustee to control his finances. He still refused to sell his beloved newspapers. At one point, to avoid outright bankruptcy, he had to accept a $1 million loan from Marion Davies, who sold all her jewelry, stocks and bonds to raise the cash for him. Davies also managed to raise him another million as a loan from Washington Herald owner Cissy Patterson. The trustee cut Hearst's annual salary to $500,000, and stopped the annual payment of $700,000 in dividends. He had to pay rent for living in his castle at San Simeon.

Legally Hearst avoided bankruptcy, although the public generally saw it as such as appraisers went through the tapestries, paintings, furniture, silver, pottery, buildings, autographs, jewelry, and other collectibles. Items in the thousands were gathered from a five-story warehouse in New York, warehouses near San Simeon containing large amounts of Greek sculpture and ceramics, and the contents of St. Donat's. His collections were sold off in a series of auctions and private sales in 1938–39. John D. Rockefeller, Junior, bought $100,000 of antique silver for his new museum at Colonial Williamsburg. The market for art and antiques had not recovered from the depression, so Hearst made an overall loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars. During this time, Hearst's friend George Loorz commented sarcastically: "He would like to start work on the outside pool [at San Simeon], start a new reservoir etc. but told me yesterday 'I want so many things but haven't got the money.' Poor fellow, let's take up a collection."

He was embarrassed in early 1939 when Time magazine published a feature which revealed he was at risk of defaulting on his mortgage for San Simeon and losing it to his creditor and publishing rival, Harry Chandler. This, however, was averted, as Chandler agreed to extend the repayment.

Final years and death

After the disastrous financial losses of the 1930s, the Hearst Company returned to profitability during the Second World War, when advertising revenues skyrocketed. Hearst, after spending much of the war at his estate of Wyntoon, returned to San Simeon full-time in 1945 and resumed building works. He also continued collecting, on a reduced scale. He threw himself into philanthropy by donating a great many works to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In 1947, Hearst left his San Simeon estate to seek medical care, which was unavailable in the remote location. He died in Beverly Hills on August 14, 1951, at the age of 88. He was interred in the Hearst family mausoleum at the Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California, which his parents had established.

His will established two charitable trusts, the Hearst Foundation and the William Randolph Hearst Foundation. By his amended will, Marion Davies inherited 170,000 shares in the Hearst Corporation, which, combined with a trust fund of 30,000 shares that Hearst had established for her in 1950, gave her a controlling interest in the corporation. This was short-lived, as she relinquished the 170,000 shares to the Corporation on October 30, 1951, retaining her original 30,000 shares and a role as an advisor. Like their father, none of Hearst's five sons graduated from college. They all followed their father into the media business, and Hearst's namesake, William Randolph Hearst Jr., became a Pulitzer Prize–winning newspaper reporter.

Criticism

In the 1890s, the already existing anti-Chinese and anti-Asian racism in San Francisco were further fanned by Hearst's anti-non-European descents, which were reflected in the rhetoric and the focus in San Francisco Examiner and one of his own signed editorials. These prejudices continued to be the mainstays throughout his journalistic career to galvanize his readers’ fears. Hearst staunchly supported the Internment of Japanese Americans during WWII and used his media power to demonize Japanese-Americans and to drum up support for the internment of Japanese-Americans.

Some media outlets have attempted to bring attention to Hearst's involvement in the prohibition of cannabis in America. Hearst collaborated with Harry J. Anslinger to ban hemp due to the threat that the burgeoning hemp paper industry posed to his major investment and market share in the paper milling industry. Due to their efforts, hemp would remain illegal to grow in the US for almost a century, not being legalized until 2018.

As Martin A. Lee and Norman Solomon noted in their 1990 book Unreliable Sources, Hearst "routinely invented sensational stories, faked interviews, ran phony pictures and distorted real events".

Hearst's use of yellow journalism techniques in his New York Journal to whip up popular support for U.S. military adventurism in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines in 1898 was also criticized in Upton Sinclair's 1919 book, The Brass Check: A Study of American Journalism. According to Sinclair, Hearst's newspapers distorted world events and deliberately tried to discredit Socialists. Another critic, Ferdinand Lundberg, extended the criticism in Imperial Hearst (1936), charging that Hearst papers accepted payments from abroad to slant the news. After the war, a further critic, George Seldes, repeated the charges in Facts and Fascism (1947). Lundberg described Hearst as "the weakest strong man and the strongest weak man in the world today... a giant with feet of clay."

In fiction

Citizen Kane

The film Citizen Kane (released on May 1, 1941) is loosely based on Hearst's life. Orson Welles and his collaborator, screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, created Kane as a composite character, among them Harold Fowler McCormick, Samuel Insull and Howard Hughes. Hearst, enraged at the idea of Citizen Kane being a thinly disguised and very unflattering portrait of him, used his massive influence and resources to prevent the film from being released—all without even having seen it. Welles and the studio RKO Pictures resisted the pressure but Hearst and his Hollywood friends ultimately succeeded in pressuring theater chains to limit showings of Citizen Kane, resulting in only moderate box-office numbers and seriously impairing Welles's career prospects.[10] The fight over the film was documented in the Academy Award-nominated documentary, The Battle Over Citizen Kane, and nearly 60 years later, HBO offered a fictionalized version of Hearst's efforts in its original production RKO 281 (1999), in which James Cromwell portrays Hearst. Citizen Kane has twice been ranked No. 1 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies: in 1998 and 2007. In 2020, David Fincher directed Mank, starring Gary Oldman as Mankiewicz, as he interacts with Hearst prior to the writing of Citizen Kane's screenplay. Charles Dance portrays Hearst in the film.

Notes

References

- ↑ "From the Archives: W. R. Hearst, 88, Dies in Beverly Hills" https://web.archive.org/web/20191215182803/https://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/archives/la-me-william-randolph-hearst-19510815-story.html Date: December 15, 2019 (original pub. August 15, 1951). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from LATimes.com September 15, 2018.

- ↑ Rodney Carlisle, "The Foreign Policy Views of an Isolationist Press Lord: W. R. Hearst & the International Crisis, 1936–41" Journal of Contemporary History (1974) 9#3 pp. 217–27.

- ↑ The Battle Over Citizen Kane https://web.archive.org/web/20170320054056/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/kane2/ Date: March 20, 2017 , PBS.

- ↑ Toledo Blade: "Paul Block: Story of success" by Jack Lessenberry https://web.archive.org/web/20141226072947/http://www.toledoblade.com/Books/2001/02/25/Early-primaries-set-the-stage-for-great-Republican-battle.html Date: December 26, 2014 January 9, 2013

- ↑ Golden, Eve (2001). Golden Images: 41 Essays on Silent Film Stars. New York: McFarland & Company, Inc, 26. ISBN 0-7864-0834-0.

- ↑ George Hearst v. Domingo Pujol, 1872, Reports of Cases Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of California, Vol. 44, pp. 230-236, Bancroft-Whitney Co., San Francisco

- ↑ California State Military Department, The California State Military Museum. Historic California Posts: Fort Hunter Liggett. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- ↑ Aircraft, Volume 1 https://web.archive.org/web/20170215172844/https://books.google.com/books?id=BBMvAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA109 Date: February 15, 2017 , 1910

- ↑ Hearst an Aviator https://web.archive.org/web/20170215180240/https://books.google.com/books?id=7yVDAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA12-IA335 Date: February 15, 2017 , Editor & Publisher, Volume 9, 1910

- ↑ Howard, James. The Complete Films of Orson Welles. (1991). New York: Citadell Press. p. 47.

Chat rooms • What links here • Copyright info • Contact information • Category:Root