Turkish bath

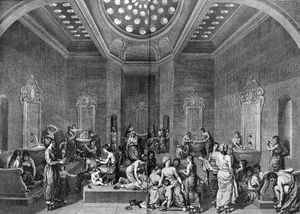

A Turkish bath (Turkish: Hamam) is the Turkish variant of a steam bath, sauna, or Russian Bath, distinguished by a focus on water, as opposed to ambient steam.

In Western Europe, the Turkish bath as a method of cleansing the body and relaxation was particularly popular during the Victorian era. The process involved in taking a Turkish bath is similar to that of a sauna but is more closely related to ancient Greek and ancient Roman bathing practices.

A person taking a Turkish bath first relaxes in a room (known as the warm room) that is heated by a continuous flow of hot, dry air allowing the bather to perspire freely. Bathers may then move to an even hotter room (known as the hot room) before splashing themselves with cold water. After performing a full body wash and receiving a massage, bathers finally retire to the cooling room for a period of relaxation.

Architecture

The Hamam combines the functionality and the structural elements of its predecessors in Anatolia, the Roman thermae and Byzantine baths, with the Central Asian Turkish tradition of steam bathing, ritual cleansing, and respect of the water. It is also known that Arabs built many of their own versions of the Greek-Roman baths that they encountered following their conquest of Alexandria. However, the Turkish bath has a more improved style and functionality from these structures that emerged as annex buildings of mosques or as the re-use of the remaining Roman baths.

The Hamams in the Ottoman culture started out as structural elements serving as annexes to mosques. However they quickly evolved into institutions unto themselves and eventually, with the works of the Ottoman architect Sinan, into monumental structural complexes, the finest example being the "Çemberlitaş Hamamı" in Istanbul, built in 1584.

Similar to its Roman predecessors, a typical Hamam consists of three basic, interconnected rooms: the sıcaklık (or hararet -caldarium), which is the hot room; the warm room (tepidarium), which is the intermediate room; and the soğukluk, which is the cool room (frigidarium).

The sıcaklık usually has a large dome decorated with small glass windows that create a half-light; it also contains a large marble stone called göbek taşı (tummy stone) at the center that the customers lie on, and niches with fountains in the corners. This room is for soaking up steam and getting scrub massages. The warm room is used for washing up with soap and water and the soğukluk is to relax, dress up, have a refreshing drink, sometimes tea, and, where available, a nap in a private cubicle after the massage. A few of the Hamams in Istanbul also contain mikvehs, ritual cleansing baths for Jewish women.

The Hamam, like its early precursors, Roman (at least pre-Christian) thermae, is not exclusive to men. Hamam complexes usually contain separate quarters for men and women or, alternatively, they are admitted at separate times. Because they were social centers as well as baths, Hamams became quite abundant during the time of the Ottoman Empire and were built in almost every Ottoman city. Integrated into daily life, they were centers for social gatherings, populated on almost every occasion with traditional entertainment (e.g. dancing and food, especially in the women's quarters) and ceremonies, such as before weddings, high holidays, celebrating newborns, beauty trips, etc.

Some accessories from Roman times survive in modern Hamams, such as the peştemal (a special cloth of silk and/or cotton to cover the body, like a pareo), nalın (wooden clogs that prevent slipping on the wet floor, or mother-of-pearl), kese (a rough mitt for massage), and sometimes jewel boxes, gilded soapboxes, mirrors, henna bowls, and perfume bottles.

Tellak (Staff)

Traditionally, the masseurs in the baths, tellak in Turkish, were young men who helped wash clients by soaping and scrubbing their bodies.

They were recruited from among the ranks of the non-Muslim subject nations of the Turkish empire, such as Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Roma, and others.

After the defeat and dismemberment of the Ottoman army in the early 20th century, the role of tellak boys was filled by adult attendants that scrub and give massages.

Operating Examples

Dating back to French rule and located in the heart of Nicosia's old town is Hamam Omerye - a true working example of Cyprus's rich culture and diversity, hard struggle, yet a sense of freedom and flexibility. The site's history dates back to the 14th century when it stood as an Augustinian church of St. Mary. Stone-built, with small domes, it is chronologically placed at around the time of Frankish and Venetian rule, approximately the same time that the city acquired its Venetian Walls. In 1571, Mustapha Pasha converted the church into a mosque, believing that this particular spot is where the Khalifa Omar rested during his visit to Lefkosia. Most of the original building was destroyed by Ottoman artillery, although the door of the main entrance still belongs to the 14th century Lusignan building, whilst remains of a later Renaissance phase can be seen at the north-eastern side of the monument. In 2003, the [EU] funded a bi-communal UNDP/UNOPS project, "Partnership for the Future", in collaboration with Nicosia Municipality and Nicosia Master Plan.

Budapest has four working Turkish Baths, all from the 16th century: Rudas Baths and Király Baths are currently open to the general public, while Racz Thermal Bath is just being reconstructed, opening 2010, and the Császár Spa Bath is not a public thermal bath.

Introduction of Turkish baths to Western Europe

The 16th century Ottoman era Rudas Baths near Budapest in Hungary. The Király Baths are from the same period. Turkish baths were introduced to the United Kingdom by David Urquhart, diplomat and sometime Member of Parliament for Stafford, who for political and personal reasons wished to popularize Turkish culture. In 1850 he wrote The Pillars of Hercules, a book about his travels in 1848 through Spain and Morocco. He described the system of dry hot-air baths used there and in the Ottoman Empire that had changed little since Roman times.

In 1856, Richard Barter read Urquhart's book and worked with him to construct a bath. They opened the first modern Turkish bath in the United Kingdom at St Ann's Hydropathic Establishment near Blarney, County Cork, Ireland. The following year, the first bath of its type to be built in England since Roman times was opened in Manchester, and the idea spread rapidly through the north of England. It reached London in July 1860 when Roger Evans, a member of one of Urquhart's Foreign Affairs Committees, opened a Turkish bath at 5 Bell Street, near Marble Arch.

During the following 150 years, well over 600 baths opened in Britain, while similar Turkish baths opened in cities in other parts of the then British Empire. Dr. John Le Gay Brereton, who had given medical advice to bathers in a Foreign Affairs Committee-owned Turkish bath in Bradford, traveled to Sydney, Australia, and opened a Turkish bath there in Spring Street in 1859, even before the bath had reached London. Canada had one by 1869, and the first one in New Zealand was opened in 1874. Urquhart's influence was felt even outside the Empire when, in 1863, Dr. Charles Shepard opened the first Turkish bath in the United States at 63 Columbia Street, Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn. Later municipal authorities introduced Turkish baths as part of swimming pool complexes, taking advantage of the fact that water-heating boilers were already on site. In the East End of London, following the influx of Jews from Europe the authorities built six Turkish baths, the last of which, at York Hall was converted in 2007 to a beauty spa.

At the time of writing (May 2010) there are just sixteen Turkish baths remaining open in the United Kingdom, although hot-air baths still thrive in the form of Russian steam baths and the Finnish sauna.

Chat rooms • What links here • Copyright info • Contact information • Category:Root