Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital

Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital is a Charitable hospital in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. It is part of the Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris and a teaching hospital of Sorbonne University.

History

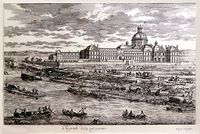

The Salpêtrière was originally a gunpowder factory (saltpetre being a constituent of gunpowder), but in 1656 at the direction of Louis XIV, it was converted into a hospice for the poor women of Paris as part of the General Hospital of Paris. This leading hospice was for women who were learning disabled, mentally ill or epileptic, and the poor. In 1657 it was incorporated with the hospice of the Pitié designed specifically for beggars' children and orphans. Sheets for hospice and military clothing were produced there by the children. Between 1663 and 1673, 240 of the women at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospice were sent on a mission to populate the Americas and help build New France. They were in the total number of 768 young women recruited during the ten-year period to become known as the "King's Daughters." The Salpêtrière was much admired for the architectural designs of Libéral Bruant with the support of Louis Le Vau. Its conversion was completed in 1669. In 1684 a women's prison was added to the site with a total capacity of 300 convicted prostitutes. It provided wretched living conditions for its inmates.

On the eve of the Revolution, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospice had become the world's largest hospice, with a capacity of 10,000 "patients" and over 300 prisoners. Until the French Revolution, the Salpêtrière had no medical function: the sick were sent to the Hôtel-Dieu hospital.

During the September massacres of 1792, the Salpêtrière was stormed on the night of 3/4 September by a mob from the impoverished working-class district of the Faubourg Saint-Marcel, with the avowed intention of releasing the detained prisoners: 134 of the prostitutes were released; twenty-five madwomen were less fortunate and were dragged, some still in their chains, into the streets and murdered.

At the very end of the 18th century, Philippe Pinel (1745–1826), a friend of the Encyclopédistes, initiated the early humanitarian reforms in treating the mentally ill. The iconic image of Pinel as the liberator of the insane was created in 1876 by Tony Robert-Fleury. Pinel's sculptural monument stands before the main entrance in Place Marie-Curie, Boulevard de L'Hôpital. Pinel was the chief physician of the Salpêtrière by 1794, in charge of a 200-bed infirmary that housed a tiny proportion of the vast indigent female population. He was succeeded by his assistant Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol (1772–1840), who, from 1817, delivered the first systematic lectures on psychiatry in France and was the chief architect of the lunacy legislation of 30 June 1838. Étienne Pariset followed Esquirol, and from 1831 till 1867, the chef d'hospice was Jean-Pierre Falret (1794–1870), who contributed much to our understanding of the bipolar disorder and folie à deux.

A regular visitor to the Salpêtrière from 1842 till his death more than thirty years later was Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne de Boulogne (1806–1875). From humble provincial origins, a long line of seafarers from Boulogne, Duchenne, became one of the outstanding medical scientists of the nineteenth century. Though he never held a senior appointment in the hospital, Duchenne nevertheless made meticulous observations on neurological patients, employing a wide range of innovative diagnostic techniques. Duchenne's clinical science stood at the technical junction of electricity, photography, and psychology, as recorded in his much admired De l'électrisation localisée with its associated atlas Album de photographies pathologiques (1855, 1862). His name is commemorated in the myopathies which he described, as well as in his 1862 masterpiece, the Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine, much consulted by Charles Darwin in the preparation of his Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). Duchenne's last major work (published in 1867) was a study of animal locomotion. He was never elected to the Academy of Sciences.

Later, when Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) took over the department, the Salpêtrière became celebrated as a neuropsychiatric teaching center, represented on canvas in 1887 by A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière by André Brouillet. In his lectures and demonstrations, the leçons du mardi, Charcot systematized the neurological examination, did much to map out the territory of modern clinical neurology, and, in a personal enthusiasm, explored its interface with psychological distress as represented in hysteria. Although Charcot insisted that hysteria could be a male disorder ("traumatic hysteria"), he is popularly remembered for his demonstrations with Louise Augustine Gleizes and Marie Wittman. Charcot had also absorbed much from Duchenne (to whom he often referred as "mon maître, Duchenne"), and his teaching activities on the Salpêtrière's wards helped to elucidate the natural history of many diseases, including neurosyphilis, epilepsy, and stroke. In his discussion of paralysis agitans, Charcot drew attention to the 1817 description by James Parkinson and suggested it be renamed Parkinson's disease. In 1882, with Charcot's encouragement, Albert Londe created a photographic department in the Salpêtriėre, producing, in collaboration with Georges Gilles de la Tourette, the Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière of 1888.

Students came from across the world to witness Charcot's clinical demonstrations: among them – in 1885 – was the 29-year-old Sigmund Freud, who translated Charcot's lectures into German and whose deconstruction of the lectures on hysteria formed the foundations of psychoanalysis. The Irish physician and politician George Sigerson published the first English translations of Charcot's Clinical Lectures (1877, 1881). Public health physician and advocate of breastfeeding Truby King traveled from New Zealand to witness Charcot and reported his clinical demonstrations as a life-changing experience. A rather negative portrait of Charcot's clinical style emerges in the 1929 autobiographical memoir – The Story of San Michele – by the Swedish physician Axel Munthe, whose early idolatry of Charcot gave way to a kind of obsessive antagonism.

The Hôpital de la Pitié, founded about 1612, was moved next to the Salpêtrière in 1911 and fused with it in 1964 to form the Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière. The Pitié-Salpêtrière is now a general teaching hospital with departments focusing on most major medical specialties.

Numerous personalities have been treated at the Salpêtrière, including Michael Schumacher, Ronaldo, Prince Rainier of Monaco, Alain Delon, Gérard Depardieu, and Valérie Trierweiler. Former president Jacques Chirac had a pacemaker fitted at the Salpêtrière in 2008. Celebrities have also died at the Pitié-Salpêtrière, including the singer Josephine Baker in 1975, following a cerebral hemorrhage; philosopher Michel Foucault in 1984 due to AIDS-related complications; Diana, Princess of Wales following a car crash in 1997; and French bicycle racer Laurent Fignon in 2010, from the metastatic spread of lung cancer (which coincidentally happened exactly thirteen years after Diana died in the same hospital).

The Brain and Spine Institute (now called Institut du Cerveau – ICM or Paris Brain Institute) has been located in the hospital since it was established in September 2010.

Buildings

Hospital Chapel

Chapelle de la Salpêtrière (Hospital Chapel), at n° 47 Boulevard de l'Hôpital is one of the masterpieces of Libéral Bruant, architect of Les Invalides. It was built around 1675, on the model of a Greek cross, and has four central chapels, each capable of holding a congregation of some 1,000 people. Its central octagonal cupola is illuminated by picture windows in circular arcs.

Philippe Pinel monument

At the main entrance to the hospital, is a large bronze monument to Philippe Pinel, who was chief physician of the Hospice from 1795 to his death in 1826. The Salpêtrière was, at the time, like a large village, with seven thousand elderly indigent and ailing women, an entrenched bureaucracy, a teeming market, and huge infirmaries. Pinel created an inoculation clinic in his service at the Salpêtrière in 1799, and the first vaccination in Paris was given there in April 1800.

Notable doctors

- Wikipedia article: Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital Notable doctors

Throughout its history, the Pitié-Salpétrière hosted notable doctors, among others:

- Philippe Pinel (1745–1826);

- Jean-Étienne Esquirol (1772–1840);

- Étienne-Jean Georget (1795–1828);

- William A. F. Browne (1805–1885);

- Bénédict Morel (1809–1873);

- Duchenne de Boulogne (1806–1875), teacher of Charcot;

- Ernest-Charles Lasègue (1816–1883);

- Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893), founder of modern neurology;

- Alfred Vulpian (1826–1893) Physician and neurologist;

- Jules Bernard Luys (1828–1897), neurologist;

- Paul Richer (1849–1933), anatomist, collaborator of Charcot;

- Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), Charcot's student in Paris and father of psychoanalysis;[20]

- Joseph Babinski (1857–1932), another Charcot's student;

- Georges Gilles de la Tourette (1857–1904), neurologist;

- Axel Munthe (1857–1940), Swedish psychiatrist, author;

- Pierre Janet (1859–1947), psychologist;

- Abel Ayerza (1861–1918), Argentinian cardiologist;

- Gérard Encausse (1865–1916), physician;

- Maria Montessori (1870–1952), pioneer in education;

- Jacques Lacan (1901–1981), psychoanalyst;

- Christian Cabrol (1925–2017), cardiac surgeon, performed Europe's first heart transplantation on 27 April 1968.

- Iradj Gandjbakhch (b. 1941), cardiac surgeon, performed Europe's first heart transplantation on 27 April 1968 along with Dr. Cabrol; fitted a pacemaker on former president Jacques Chirac in 2008.

External links

- Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital (in Japanese)

- History of La Salpêtrière

- Salpêtrière Hospital records, 1859–1942 (inclusive), 1900–1919 (bulk), HMS c30. Harvard Medical Library, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine,

- Center for the History of Medicine, Harvard Medical School

Chat rooms • What links here • Copyright info • Contact information • Category:Root