Al Jolson

| Al Jolson | ||

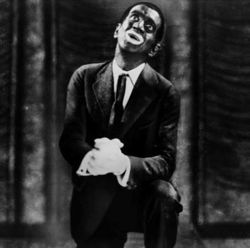

Jolson in 1929 | ||

| Background information | ||

| Born as: | Asa Yoelson | |

| Other names: | Jolie | |

| Born | May 26, 1886 Sredniki, Kovno Governorate (Lithunia) Russia | |

| Died | Oct 23, 1950 - at age 63 San Francisco, California, U.S. | |

| Spouse(s): | Henrietta Keller (1907 - 1919) divorced Alma Osbourne (1922 - 1928) divorced Ruby Keeler (1928 - 1940) divorced Erle Galbraith (1945 - ) | |

| Children: | 3 (all adopted) | |

| Occupation: | ||

| Label{s} |

| |

| Years active | 1904–1950 | |

| Website: | jolson.org | |

| Genre(s): |

| |

Al Jolson (born Asa Yoelson; ✦May 26, 1886 – †October 23, 1950) was a Lithuanian-American singer, comedian, actor, and vaudevillian. He was one of the United State's most famous and highest-paid stars of the 1920s, and was self-billed as "The World's Greatest Entertainer." Jolson was known for his "shamelessly sentimental, melodramatic approach" towards performing, as well as for popularizing many of the songs he sang. Jolson has been referred to by modern critics as "the king of blackface performers."

Although best remembered today as the star of the first talking picture, The Jazz Singer (1927), he starred in a series of successful musical films during the 1930s. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he was the first star to entertain troops overseas during World War II. After a period of inactivity, his stardom returned with The Jolson Story (1946), in which Larry Parks played Jolson, with the singer dubbing for Parks. The formula was repeated in a sequel, Jolson Sings Again (1949). In 1950, he again became the first star to entertain GIs on active service in the Korean War, performing 42 shows in 16 days. He died weeks after returning to the U.S., partly owing to the physical exhaustion from the performance schedule. Defense Secretary George Marshall posthumously awarded him the Medal for Merit.

According to music historian Larry Stempel, "No one had heard anything quite like it before on Broadway." Stephen Banfield wrote that Jolson's style was "arguably the single most important factor in defining the modern musical."

With his dynamic style of singing jazz and blues, he became widely successful by extracting traditionally African-American music and popularizing it for white American audiences who would be unwilling to listen to it when performed by black artists. Despite his promotion and perpetuation of black stereotypes, his work was often well-regarded by black publications. He has been credited for fighting against black discrimination on Broadway as early as 1911. In an essay written in 2000, music critic Ted Gioia remarked, "If blackface has its shameful poster boy, it is Al Jolson", showcasing Jolson's complex legacy in American society.

Performing in blackface

Jolson often performed in blackface makeup. Performing in blackface makeup was a theatrical convention of many entertainers at the beginning of the 20th century, originating in the minstrel show. According to film historian Eric Lott:

- "For the white minstrel man to put on the cultural forms of 'blackness' was to engage in a complex affair of manly mimicry.... To wear or even enjoy blackface was literally, for a time, to become black, to inherit the cool, virility, humility, abandon, or gaité de coeur (tr: happy heart) that were the prime components of white ideologies of black manhood."

In the retrospective view of a later era, however, the use of blackface has come to be viewed as implicit racism. Music critic Ted Gioia, commenting on Jolson's use of blackface, wrote:

- "Blackface evokes memories of the most unpleasant side of racial relations and of an age in which white entertainers used the makeup to ridicule black Americans while brazenly borrowing from the rich black musical traditions that were rarely allowed direct expression in mainstream society. This is heavy baggage for Al Jolson.

As metaphor of mutual suffering

Historians have described Jolson's blackface and singing style as metaphors for Jewish and black suffering throughout history. Jolson's first film, The Jazz Singer, for instance, is described by historian Michael Alexander as an expression of the liturgical music of Jews with the "imagined music of African Americans", noting that "prayer and jazz become metaphors for Jews and blacks." Playwright Samson Raphaelson, after seeing Jolson perform his stage show Robinson Crusoe, stated that "he had an epiphany: 'My God, this isn't a jazz singer', he said. 'This is a cantor!'" The image of the blackfaced cantor remained in Raphaelson's mind when he conceived of the story which led to The Jazz Singer.

Upon the film's release, the first full-length sound picture, film reviewers saw the symbolism and metaphors portrayed by Jolson in his role as the son of a cantor wanting to become a "jazz singer":

Is there any incongruity in this Jewish boy with his face painted like a Southern Negro singing in the Negro dialect? No, there is not. Indeed, I detected again and again the minor key of Jewish music, the wail of the Chazan, the cry of anguish of a people who had suffered. The son of a line of rabbis well knows how to sing the songs of the most cruelly wronged people in the world's history.

According to Alexander, Eastern European Jews were uniquely qualified to understand the music, noting how Jolson himself made the comparison of Jewish and African-American suffering in a new land in his film Big Boy: In a blackface portrayal of a former slave, he leads a group of recently freed slaves, played by black actors, in verses of the classic slave spiritual "Go Down Moses". One reviewer of the film expressed how Jolson's blackface added significance to his role: When one hears Jolson's jazz songs, one realizes that jazz is the new prayer of the American masses, and Al Jolson is their cantor. The Negro makeup in which he expresses his misery is the appropriate talis [prayer shawl] for such a communal leader.

Many in the black community welcomed The Jazz Singer and saw it as a vehicle to gain access to the stage. Audiences at Harlem's Lafayette Theater cried during the film, and Harlem's newspaper, Amsterdam News, called it "one of the greatest pictures ever produced." For Jolson, it wrote: "Every colored performer is proud of him."

Relations with African Americans

Jolson's legacy as the most popular performer of blackface routines was complemented by his relationships with African-Americans and his appreciation and use of African-American cultural trends. Jolson first heard jazz, blues, and ragtime in the alleys of New Orleans. He enjoyed singing jazz, often performing in blackface, especially in the songs he made popular such as "Swanee", "My Mammy", and "Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody".

As a Jewish immigrant and America's most famous and highest-paid entertainer, he may have had the incentive and resources to help improve racial attitudes. While The Birth of a Nation glorified white supremacy and the KKK, Jolson chose to star in The Jazz Singer, which defied racial bigotry by introducing black musicians to audiences worldwide.

While growing up, Jolson had many black friends, including Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, who became a prominent tap dancer. As early as 1911, at the age of 25, Jolson was noted for fighting discrimination on Broadway and later in his movies. In 1924, he promoted the play Appearances by Garland Anderson, which became the first production with an all-black cast produced on Broadway. He brought a black dance team from San Francisco that he tried to put in a Broadway show. He demanded equal treatment for Cab Calloway, with whom he performed duets in the movie The Singing Kid.

Jolson read in the newspaper that songwriters Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, neither of whom he had ever heard of, were refused service at a Connecticut restaurant because of their race. He tracked them down and took them out to dinner, "insisting he'd punch anyone in the nose who tried to kick us out!" According to biographer Al Rose, Jolson and Blake became friends and went to boxing matches together.

Film historian Charles Musser notes, "African Americans' embrace of Jolson was not a spontaneous reaction to his appearance in talking pictures. In an era when African Americans did not have to go looking for enemies, Jolson was perceived a friend."

Jeni LeGon, a black female tap dancer, recalls her life as a film dancer: "But of course, in those times it was a 'black-and-white world.' You didn't associate too much socially with any of the stars. You saw them at the studio, you know, nice—but they didn't invite. The only ones that ever invited us home for a visit was Al Jolson and Ruby Keeler."

British performer Brian Conley, former star of the 1995 British play Jolson, stated during an interview, "I found out Jolson was actually a hero to the black people of America. At his funeral, black actors lined the way, they really appreciated what he'd done for them."

Noble Sissle, who was by then president of the Negro Actors Guild, represented that organization at his funeral.

Jolson's physical expressiveness also affected the music styles of some black performers. Music historian Bob Gulla writes that "the most critical influence in Jackie Wilson's young life was Al Jolson." He points out that Wilson's ideas of what a stage performer could do to keep their act an "exciting" and "thrilling performance" was shaped by Jolson's acts, "full of wild writhing and excessive theatrics". Wilson felt that Jolson "should be considered the stylistic [forefather] of rock and roll."

According to the St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture: "Almost single-handedly, Jolson helped to introduce African-American musical innovations like jazz, ragtime, and the blues to white audiences ... [and] paved the way for African-American performers like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, and Ethel Waters ... to bridge the cultural gap between black and white America."

Amiri Baraka wrote, "the entrance of the white man into jazz ... did at least bring him much closer to the Negro." He points out that "the acceptance of jazz by whites marks a crucial moment when an aspect of black culture had become an essential part of American culture."

War tours

World War II

Japanese bombs on Pearl Harbor shook Jolson out of continuing moods of lethargy due to years of little activity and "... he dedicated himself to a new mission in life.... Even before the U.S.O. began to set up a formal program overseas, Jolson was deluging War and Navy Department brass with phone calls and wires. He requested permission to go anywhere in the world where there was an American serviceman who wouldn't mind listening to 'Sonny Boy' or 'Mammy'.... [and] early in 1942, Jolson became the first star to perform at a GI base in World War II".

From a 1942 interview in The New York Times: "When the war started ... [I] felt that it was up to me to do something, and the only thing I know is show business. I went around during the last war and I saw that the boys needed something besides chow and drills. I knew the same was true today, so I told the people in Washington that I would go anywhere and do an act for the Army." Shortly after the war began, he wrote a letter to Steven Early, press secretary to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, volunteering "to head a committee for the entertainment of soldiers and said that he "would work without pay ... [and] would gladly assist in the organization to be set up for this purpose". A few weeks later, he received his first tour schedule from the newly formed United Services Organization (USO), "the group his letter to Early had helped create".

- He did as many as four shows a day in the jungle outposts of Central America and covered the string of U.S. Naval bases. He paid for part of the transportation out of his own pocket. Upon doing his first, and unannounced, show in England in 1942, the reporter for the Hartford Courant wrote, "... it was a panic. And pandemonium ... when he was done the applause that shook that soldier-packed room was like bombs falling again in Shaftsbury Avenue."

From an article in The New York Times:

- He [Jolson] has been to more Army camps and played to more soldiers than any other entertainer. He has crossed the Atlantic by plane to take song and cheer to the troops in Britain and Northern Ireland. He has flown to the cold wastes of Alaska and the steaming forests of Trinidad. He has called at Dutch‑like Curaçao. Nearly every camp in this country has heard him sing and tell funny stories.

Some of the unusual hardships of performing to active troops were described in an article he wrote for Variety, in 1942:

- In order to entertain all the boys ... it became necessary for us to give shows in foxholes, gun emplacements, dugouts, to construction groups on military roads; in fact, any place where two or more soldiers were gathered together, it automatically became a Winter Garden for me, and I would give a show.

After returning from a tour of overseas bases, the Regimental Hostess at one camp wrote to Jolson, Allow me to say on behalf of all the soldiers of the 33rd Infantry that you coming here is quite the most wonderful thing that has ever happened to us, and we think you're tops, not only as a performer, but as a person. We unanimously elect you Public Morale Lifter No. 1 of the U.S Army.

Jolson was officially enlisted in the United Services Organization (USO), the organization which provided entertainment for American troops who served in combat overseas. Because he was over the age of 45, he received a "Specialist" rating that permitted him to wear a uniform and be given the standing of an officer. While touring in the Pacific, Jolson contracted malaria and had to have his left lung surgically removed. In 1946, during a nationally broadcast testimonial dinner in New York City, given on his behalf, he received a special tribute from the American Veterans Committee in honor of his volunteer services during World War II. In 1949, the movie Jolson Sings Again recreated some scenes showing Jolson during his war tours.

Korean War

In 1950, according to Jolson's biographer Michael Freedland, "the United States answered the call of the United Nations Security Council ... and had gone to fight the North Koreans.... [Jolson] rang the White House again. 'I'm gonna go to Korea,' he told a startled official on the phone. 'No one seems to know anything about the USO, and it's up to President Truman to get me there.' He was promised that President Truman and General MacArthur, who had taken command of the Korean front, would get to hear of his offer. But for four weeks there was nothing.... Finally, Louis A. Johnson, Secretary of Defense, sent Jolson a telegram. 'Sorry for delay but regret no funds for entertainment – STOP; USO disbanded – STOP.' The message was as much an assault on the Jolson sense of patriotism as the actual crossing of the 38th Parallel had been. 'What are they talkin' about', he thundered. 'Funds? Who needs funds? I got funds! I'll pay myself!'"

On September 17, 1950, a dispatch from 8th Army Headquarters, Korea, announced, "Al Jolson, the first top-flight entertainer to reach the war-front, landed here today by plane from Los Angeles...." Jolson traveled to Korea at his own expense. "[A]nd a lean, smiling Jolson drove himself without letup through 42 shows in 16 days."

Before returning to the U.S., General Douglas MacArthur, leader of UN forces, gave him a medallion inscribed "To Al Jolson from Special Services in appreciation of entertainment of armed forces personnel ‑ Far East Command", with his entire itinerary inscribed on the reverse side. A few months later, an important bridge, named the "Al Jolson Bridge", was used to withdraw the bulk of American troops from North Korea. The bridge was the last remaining of three bridges across the Han River and was used to evacuate UN forces. It was demolished by UN forces after the army made it safely across in order to prevent the Chinese from crossing.

Alistair Cooke wrote, "He [Jolson] had one last hour of glory. He offered to fly to Korea and entertain the troops hemmed in on the United Nations precarious August bridgehead. The troops yelled for his appearance. He went down on his knee again and sang 'Mammy', and the troops wept and cheered. When he was asked what Korea was like he warmly answered, 'I am going to get back my income tax returns and see if I paid enough.'" Jack Benny, who went to Korea the following year, noted that an amphitheater in Korea where troops were entertained, was named the "Al Jolson Bowl".

Ten days after returning from Korea, he agreed with RKO Pictures producers Jerry Wald and Norman Krasna to star in Stars and Stripes for Ever, a movie about a USO troupe in the South Pacific during World War II. The screenplay was to be written by Herbert Baker and to co-star Dinah Shore. But Jolson had overexerted himself in Korea, especially for a man who was missing a lung. Two weeks after signing the agreement, he died of a heart attack in San Francisco. A few months after his death, Defense Secretary George Marshall presented the Medal for Merit for Jolson, "to whom this country owes a debt which cannot be repaid". The medal, carrying a citation noting that Jolson's "contribution to the U.N. action in Korea was made at the expense of his life", was presented to Jolson's adopted son as Jolson's widow looked on.

Personal life

Despite their close relationship while growing up, Harry Jolson (Al's older brother) did show some disdain for Jolson's success over the years. Even during their time with Jack Palmer, Jolson was rising in popularity while Harry was fading. After separating from "Al and Jack", Harry's career in show business sank. On one occasion Harry offered to be Jolson's agent, but Jolson rejected the offer, worried about the pressure he would face from his producers for hiring his brother. Shortly after Harry's wife Lillian died in 1948, the brothers became close once again.

Jolson's first marriage, to Henrietta Keller (1889–1967), took place in Alameda, California, on September 20, 1907. His name was given as Albert Jolson. The couple divorced in 1919. In 1920, he began a relationship with Broadway actress Alma Osbourne (known professionally as Ethel Delmar); the two were married in August 1922; she divorced Jolson in 1928.

In the summer of 1928, Jolson met young tap dancer, and later actress, Ruby Keeler in Los Angeles (Jolson would claim it was at Texas Guinan's night club) and was dazzled by her on sight. Three weeks later, Jolson saw a production of George M. Cohan's Rise of Rosie O'Reilly, and noticed she was in the show's cast. Now knowing she was going about her Broadway career, Jolson attended another one of her shows, Show Girl, and rose from the audience and engaged in her duet of "Liza". After this moment, the show's producer, Florenz Ziegfeld, asked Jolson to join the cast and continue to sing duets with Keeler. Jolson accepted Ziegfeld's offer, and during their tour with Ziegfeld, the two started dating and were married on September 21, 1928. In 1935, Al and Ruby adopted a son, Jolson's first child, whom they named "Al Jolson Jr." In 1939, however—despite a marriage that was considered to be more successful than his previous ones—Keeler left Jolson. After their 1940 divorce, she remarried to John Homer Lowe, with whom she would have four children and remain married until his death in 1969.

In 1944, while giving a show at a military hospital in Hot Springs, Arkansas, Jolson met a young X-ray technologist, Erle Galbraith. He became fascinated with her, and more than a year later, he was able to track her down and hired her as an actress while he served as a producer at Columbia Pictures. After Jolson, whose health was still scarred from his previous battle with malaria, was hospitalized in the winter of 1945, Erle visited him, and the two quickly began a relationship. They were married on March 22, 1945. During their marriage, the Jolson's adopted two children, Asa Jr. (born 1948) and Alicia (born 1949), and remained married until his death in 1950.

After a year and a half of marriage, his new wife had never seen him perform in front of an audience, and the first occasion came unplanned. As told by actor-comedian Alan King, it happened during a dinner by the New York Friars' Club at the Waldorf Astoria in 1946 to honor the career of Sophie Tucker. Jolson and his wife were in the audience with a thousand others, and George Jessel was the emcee.

Without warning, during the middle of the show, Jessel said, "Ladies and gentlemen, this is the easiest introduction I ever had to make. The world's greatest entertainer, Al Jolson." King recalls what happened next: The place is going wild. Jolson gets up, takes a bow, sits down ... people start banging with their feet, and he gets up, takes another bow, sits down again. It's chaos, and slowly, he seems to relent. He walks up onto the stage ... kids around with Sophie and gets a few laughs, but the people are yelling, 'Sing! Sing! Sing!'.... Then he says, 'I'd like to introduce you to my bride,' and this lovely young thing gets up and takes a bow. The audience doesn't care about the bride, they don't even care about Sophie Tucker. 'Sing! Sing! Sing!' they're screaming again. 'My wife has never seen me entertain', Jolson says, and looks over toward Lester Lanin, the orchestra leader: 'Maestro, is it true what they say about Dixie?'

Death

While playing cards in his suite at the St. Francis Hotel at 335 Powell Street in San Francisco, Jolson died of a massive heart attack on October 23, 1950. His last words were said to be "Oh ... oh, I'm going." He was 64.

After his wife received the news of his death by phone, she went into shock and required family members to stay with her. At the funeral, police estimated that upwards of 20,000 people showed up, despite the threat of rain. It became one of the biggest funerals in show business history. Celebrities paid tribute: Bob Hope, speaking from Korea via shortwave radio, said the world had lost "not only a great entertainer, but also a great citizen". Larry Parks said that the world had "lost not only its greatest entertainer, but a great American as well. He was a casualty of the [Korean] war." Scripps-Howard newspapers drew a pair of white gloves on a black background. The caption read, "The Song Is Ended."

Newspaper columnist and radio reporter Walter Winchell said:

- He was the first to entertain troops in World War Two, contracted malaria and lost a lung. Then in his upper sixties he was again the first to offer his singing gifts for bringing solace to the wounded and weary in Korea.

- Today we know the exertion of his journey to Korea took a greater toll of his strength than perhaps even he realized. But he considered it his duty as an American to be there, and that was all that mattered to him. Jolson died in a San Francisco hotel. Yet he was as much a battle casualty as any American soldier who has fallen on the rocky slopes of Korea.... A star for more than 40 years, he earned his most glorious star rating at the end—a gold star.

Friend George Jessel said during part of his eulogy:

- The history of the world does not say enough about how important the song and the singer have been. But history must record the name Jolson, who in the twilight of his life sang his heart out in a foreign land, to the wounded and to the valiant. I am proud to have basked in the sunlight of his greatness, to have been part of his time.

He was interred in the Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery in Culver City, California. Jolson's widow purchased a plot at Hillside and commissioned his mausoleum to be designed by well-known black architect Paul Williams. The six-pillar marble structure is topped by a dome, next to a three-quarter-size bronze statue of Jolson, eternally resting on one knee, arms outstretched, apparently ready to break into another verse of "Mammy". The inside of the dome features a huge mosaic of Moses holding the tablets containing the Ten Commandments, and identifies Jolson as "The Sweet Singer of Israel" and "The Man Raised Up High".

On the day he died, Broadway dimmed its lights in Jolson's honor, and radio stations worldwide paid tributes. Soon after his death, the BBC presented a special program entitled Jolson Sings On. His death unleashed tributes from all over the world, including several eulogies from friends, including George Jessel, Walter Winchell, and Eddie Cantor. He contributed millions to Jewish and other charities in his will.

Filmography

- Wikipedia article: Al Jolson filmography

- Wikipedia article: Al Jolson Legacy and influence

| Note: Al Jolson was a volunteer at the Hollywood Canteen |

| Note: Al Jolson was a volunteer at the USO |

- Wikipedia article: Al Jolson

External links

- Al Jolson at the Internet Broadway Database

- Al Jolson at the Internet Movie Database

- International Al Jolson Society

- Al Jolson recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings.

- Newsreel at the Internet Archive, including Jolson's death and funeral

- The Museum of Family History

- Al Jolson at Virtual History

- Radio programs at Zoot Radio

- Documentary about Al Jolson and the making of The Jazz Singer

Chat rooms • What links here • Copyright info • Contact information • Category:Root