Court entertainment: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "{{Header| 03/24}} == Court entertainment == Imperial and royal courts have provided training grounds and support for professional entertainers, with different cultures using palaces, castles and forts in different ways. In the Maya city states, for example, "spectacles often took place in large plazas in front of palaces; the crowds gathered either there or in designated places from which they could watch at a distance."<ref name=Walthall>{{cite book|title=Servants of t...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Imperial and royal courts have provided training grounds and support for professional entertainers, with different cultures using palaces, castles and forts in different ways. In the Maya city states, for example, "spectacles often took place in large plazas in front of palaces; the crowds gathered either there or in designated places from which they could watch at a distance."<ref name=Walthall>{{cite book|title=Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History|year=2008|publisher=University of California Press|location=London|isbn=978-0-520-25443-5|editor=Walthall, Anne|ref=CITEREFWalthall2008}} pp. 4–5.</ref> Court entertainments also crossed cultures. For example, the durbar was introduced to India by the Mughal emperors<ref group="def">The emperors of the '''Mughal Empire''', who were all members of the Timurid dynasty, ruled over the empire from its inception in 1526 to its dissolution in 1857. </ref>, and passed onto the British Empire, which then followed Indian tradition: "institutions, titles, customs, ceremonies by which a Maharaja<ref group="def">'''Mahārāja''' is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king", or "high king". A few ruled states informally called empires, including the ruler Raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, and Chandragupta Maurya.</ref> or Nawab<ref group="def">'''Nawab''', also spelled Nawaab, Navaab, Navab, Nowab, Nabob, Nawaabshah, Nawabshah or Nobab, is a royal title indicating a sovereign ruler, often of a South Asian state, in many ways comparable to the western title of Prince. </ref> were installed ... the exchange of official presents ... the order of precedence", for example, were "all inherited from ... the Emperors of Delhi".<ref name="Indian Princes">{{cite book|last1=Allen|first1=Charles|author-link = Charles Allen (writer)|last2 = Dwivedi|first2=Sharada|author-link2 = Sharada Dwivedi|title=Lives of the Indian Princes|year=1984|publisher=Century Publishing|location=London|isbn=978-0-7126-0910-4|page=210}}</ref> In Korea, the "court entertainment dance" was "originally performed in the palace for entertainment at court banquets." <ref name="Van Zile">{{cite book|last=Van Zile|first=Judy|title=Perspectives on Korean Dance|year=2001|publisher=Wesleyan University Press|location=Middletown, CN|isbn=978-0-8195-6494-8|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/perspectivesonko0000vanz}} p. 36.</ref> | Imperial and royal courts have provided training grounds and support for professional entertainers, with different cultures using palaces, castles and forts in different ways. In the Maya city states, for example, "spectacles often took place in large plazas in front of palaces; the crowds gathered either there or in designated places from which they could watch at a distance."<ref name=Walthall>{{cite book|title=Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History|year=2008|publisher=University of California Press|location=London|isbn=978-0-520-25443-5|editor=Walthall, Anne|ref=CITEREFWalthall2008}} pp. 4–5.</ref> Court entertainments also crossed cultures. For example, the durbar was introduced to India by the Mughal emperors<ref group="def">The emperors of the '''Mughal Empire''', who were all members of the Timurid dynasty, ruled over the empire from its inception in 1526 to its dissolution in 1857. </ref>, and passed onto the British Empire, which then followed Indian tradition: "institutions, titles, customs, ceremonies by which a Maharaja<ref group="def">'''Mahārāja''' is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king", or "high king". A few ruled states informally called empires, including the ruler Raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, and Chandragupta Maurya.</ref> or Nawab<ref group="def">'''Nawab''', also spelled Nawaab, Navaab, Navab, Nowab, Nabob, Nawaabshah, Nawabshah or Nobab, is a royal title indicating a sovereign ruler, often of a South Asian state, in many ways comparable to the western title of Prince. </ref> were installed ... the exchange of official presents ... the order of precedence", for example, were "all inherited from ... the Emperors of Delhi".<ref name="Indian Princes">{{cite book|last1=Allen|first1=Charles|author-link = Charles Allen (writer)|last2 = Dwivedi|first2=Sharada|author-link2 = Sharada Dwivedi|title=Lives of the Indian Princes|year=1984|publisher=Century Publishing|location=London|isbn=978-0-7126-0910-4|page=210}}</ref> In Korea, the "court entertainment dance" was "originally performed in the palace for entertainment at court banquets." <ref name="Van Zile">{{cite book|last=Van Zile|first=Judy|title=Perspectives on Korean Dance|year=2001|publisher=Wesleyan University Press|location=Middletown, CN|isbn=978-0-8195-6494-8|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/perspectivesonko0000vanz}} p. 36.</ref> | ||

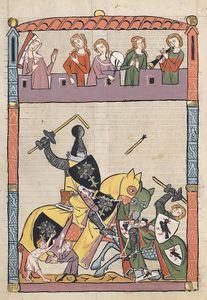

Court entertainment often moved from being associated with the court to more general use among commoners<ref group="def">A '''commoner''', also known as the common man, commoners, the common people or the masses, was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither royalty, nobility, nor any part of the aristocracy.</ref>. This was the case with "masked dance-dramas" in Korea, which "originated in conjunction with village [[Shamanism|shaman]] rituals and eventually became largely an entertainment form for commoners". Nautch dancers in the Mughal Empire performed in Indian courts and palaces. Another evolution, similar to that from courtly entertainment to common practice, was the transition from religious ritual to secular entertainment, such as happened during the Goryeo dynasty <ref group="def">'''Goryeo''' was a Korean state founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392. </ref>with the Narye festival. Originally "solely religious or ritualistic, a secular component was added at the conclusion". | Court entertainment often moved from being associated with the court to more general use among commoners<ref group="def">A '''commoner''', also known as the common man, commoners, the common people or the masses, was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither royalty, nobility, nor any part of the aristocracy.</ref>. This was the case with "masked dance-dramas" in Korea, which "originated in conjunction with village [[Shamanism|shaman]] rituals and eventually became largely an entertainment form for commoners". Nautch dancers in the Mughal Empire performed in Indian courts and palaces. Another evolution, similar to that from courtly entertainment to common practice, was the transition from religious ritual to secular entertainment, such as happened during the Goryeo dynasty <ref group="def">'''Goryeo''' was a Korean state founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392. </ref>with the Narye festival. Originally "solely religious or ritualistic, a secular component was added at the conclusion".<ref group = "ref">Van Zile|2001|p=69</ref> Former courtly entertainments, such as [[jousting]], often also survived in children's games. | ||

In some courts, such as those during the [[Byzantine Empire]], the genders were segregated among the upper classes, so that "at least before the period of the Komnenoi" (1081–1185) men were separated from women at ceremonies where there was entertainment such as receptions and banquets.<ref name=Garland>{{cite book|last=Garland|first=Lynda|title=Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience 800–1200|year=2006|publisher=Ashgate Publishing Limited|location=Aldershot, Hampshire|isbn=978-0-7546-5737-8|pages=177–178}}</ref> | In some courts, such as those during the [[Byzantine Empire]], the genders were segregated among the upper classes, so that "at least before the period of the Komnenoi" (1081–1185) men were separated from women at ceremonies where there was entertainment such as receptions and banquets.<ref name=Garland>{{cite book|last=Garland|first=Lynda|title=Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience 800–1200|year=2006|publisher=Ashgate Publishing Limited|location=Aldershot, Hampshire|isbn=978-0-7546-5737-8|pages=177–178}}</ref> | ||

Court ceremonies, palace banquets and the spectacles associated with them, have been used not only to entertain but also to demonstrate wealth and power. Such events reinforce the relationship between ruler and ruled; between those with power and those without, serving to "dramatise the differences between ordinary families and that of the ruler". | Court ceremonies, palace banquets and the spectacles associated with them, have been used not only to entertain but also to demonstrate wealth and power. Such events reinforce the relationship between ruler and ruled; between those with power and those without, serving to "dramatise the differences between ordinary families and that of the ruler".<ref group = "ref">Walthall (2008)</ref> This is the case as much as for traditional courts as it is for contemporary ceremonials, such as the [[Hong Kong handover ceremony]] in 1997, at which an array of entertainments (including a banquet, a parade, fireworks, a festival performance and an art spectacle) were put to the service of highlighting a change in political power. Court entertainments were typically performed for royalty and courtiers as well as "for the pleasure of local and visiting dignitaries".<ref group = "ref">Van Zile (2001) p=6</ref> Royal courts, such as the Korean one, also supported traditional dances.<ref group = "ref">Van Zile (2001) p=6</ref> In Sudan, musical instruments such as the so-called "slit" or "talking" drums, once "part of the court orchestra of a powerful chief", had multiple purposes: they were used to make music; "speak" at ceremonies; mark community events; send long-distance messages; and call men to hunt or war. | ||

<ref group="ref">{{cite web|last=McGregor|first=Neil|title=Episode 94: Sudanese Slit Drum (Transcript)|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about/transcripts/episode94/|work=History of the World in 100 Objects|publisher=BBC Radio 4/British Museum|access-date=6 February 2013|archive-date=15 June 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130615000158/http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about/transcripts/episode94/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref group="ref">{{cite book|last=McGregor|first=Neil|title=A History of the World in 100 objects|year=2010|publisher=Allen Lane|location=London|isbn=978-1-84614-413-4|pages=613–}}</ref><ref group="ref">{{cite web| url = https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/FMgugdskR7eaWj_ST2fAeQ| title = British Museum catalogue image of Sudanese slit drum| access-date = 20 December 2019| archive-date = 27 December 2019| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20191227151825/http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/FMgugdskR7eaWj_ST2fAeQ| url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

Courtly entertainments also demonstrate the complex relationship between entertainer and spectator: individuals may be either an entertainer or part of the audience, or they may swap roles even during the course of one entertainment. In the court at the [[Palace of Versailles]], "thousands of courtiers, including men and women who inhabited its apartments, acted as both performers and spectators in daily rituals that reinforced the status hierarchy". | Courtly entertainments also demonstrate the complex relationship between entertainer and spectator: individuals may be either an entertainer or part of the audience, or they may swap roles even during the course of one entertainment. In the court at the [[Palace of Versailles]], "thousands of courtiers, including men and women who inhabited its apartments, acted as both performers and spectators in daily rituals that reinforced the status hierarchy".<ref group = "ref">Walthall|2008</ref> | ||

Like court entertainment, royal occasions such as coronations and weddings provided opportunities to entertain both the aristocracy and the people. For example, the splendid 1595 [[Accession Day]] celebrations of Elizabeth I of England offered tournaments and jousting and other events performed "not only before the assembled court, in all their finery, but also before thousands of Londoners eager for a good day's entertainment. Entry for the day's events at the Tiltyard<ref group="def">A '''tiltyard''' (or tilt yard or tilt-yard) was an enclosed courtyard for jousting. Tiltyards were a common feature of Tudor era castles and palaces. The Horse Guards Parade in London was formerly the tiltyard constructed by Henry VIII as an entertainment venue adjacent to Whitehall Palace; it was the site of the Accession Day tilts in the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I.</ref> in [[Palace of Whitehall|Whitehall]] was set at 12d (12 pence)".<ref name=Bevington>{{cite book|title=The Politics of the Stuart Court Masque|year=1998|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-59436-3|author=Holbrook, Peter|editor=Bevington, David|pages=42–43}}</ref> | Like court entertainment, royal occasions such as coronations and weddings provided opportunities to entertain both the aristocracy and the people. For example, the splendid 1595 [[Accession Day]] celebrations of Elizabeth I of England offered tournaments and jousting and other events performed "not only before the assembled court, in all their finery, but also before thousands of Londoners eager for a good day's entertainment. Entry for the day's events at the Tiltyard<ref group="def">A '''tiltyard''' (or tilt yard or tilt-yard) was an enclosed courtyard for jousting. Tiltyards were a common feature of Tudor era castles and palaces. The Horse Guards Parade in London was formerly the tiltyard constructed by Henry VIII as an entertainment venue adjacent to Whitehall Palace; it was the site of the Accession Day tilts in the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I.</ref> in [[Palace of Whitehall|Whitehall]] was set at 12d (12 pence)".<ref name=Bevington>{{cite book|title=The Politics of the Stuart Court Masque|year=1998|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-59436-3|author=Holbrook, Peter|editor=Bevington, David|pages=42–43}}</ref> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 23: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<References /> | <References /> | ||

== Definitions == | === Group Ref === | ||

<references group="ref" /> | |||

=== Definitions === | |||

<references group="def" /> | <references group="def" /> | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

Revision as of 00:49, 26 March 2024

Court entertainment

Imperial and royal courts have provided training grounds and support for professional entertainers, with different cultures using palaces, castles and forts in different ways. In the Maya city states, for example, "spectacles often took place in large plazas in front of palaces; the crowds gathered either there or in designated places from which they could watch at a distance."[1] Court entertainments also crossed cultures. For example, the durbar was introduced to India by the Mughal emperors[def 1], and passed onto the British Empire, which then followed Indian tradition: "institutions, titles, customs, ceremonies by which a Maharaja[def 2] or Nawab[def 3] were installed ... the exchange of official presents ... the order of precedence", for example, were "all inherited from ... the Emperors of Delhi".[2] In Korea, the "court entertainment dance" was "originally performed in the palace for entertainment at court banquets." [3]

Court entertainment often moved from being associated with the court to more general use among commoners[def 4]. This was the case with "masked dance-dramas" in Korea, which "originated in conjunction with village shaman rituals and eventually became largely an entertainment form for commoners". Nautch dancers in the Mughal Empire performed in Indian courts and palaces. Another evolution, similar to that from courtly entertainment to common practice, was the transition from religious ritual to secular entertainment, such as happened during the Goryeo dynasty [def 5]with the Narye festival. Originally "solely religious or ritualistic, a secular component was added at the conclusion".[ref 1] Former courtly entertainments, such as jousting, often also survived in children's games.

In some courts, such as those during the Byzantine Empire, the genders were segregated among the upper classes, so that "at least before the period of the Komnenoi" (1081–1185) men were separated from women at ceremonies where there was entertainment such as receptions and banquets.[4]

Court ceremonies, palace banquets and the spectacles associated with them, have been used not only to entertain but also to demonstrate wealth and power. Such events reinforce the relationship between ruler and ruled; between those with power and those without, serving to "dramatise the differences between ordinary families and that of the ruler".[ref 2] This is the case as much as for traditional courts as it is for contemporary ceremonials, such as the Hong Kong handover ceremony in 1997, at which an array of entertainments (including a banquet, a parade, fireworks, a festival performance and an art spectacle) were put to the service of highlighting a change in political power. Court entertainments were typically performed for royalty and courtiers as well as "for the pleasure of local and visiting dignitaries".[ref 3] Royal courts, such as the Korean one, also supported traditional dances.[ref 4] In Sudan, musical instruments such as the so-called "slit" or "talking" drums, once "part of the court orchestra of a powerful chief", had multiple purposes: they were used to make music; "speak" at ceremonies; mark community events; send long-distance messages; and call men to hunt or war. [ref 5][ref 6][ref 7]

Courtly entertainments also demonstrate the complex relationship between entertainer and spectator: individuals may be either an entertainer or part of the audience, or they may swap roles even during the course of one entertainment. In the court at the Palace of Versailles, "thousands of courtiers, including men and women who inhabited its apartments, acted as both performers and spectators in daily rituals that reinforced the status hierarchy".[ref 8]

Like court entertainment, royal occasions such as coronations and weddings provided opportunities to entertain both the aristocracy and the people. For example, the splendid 1595 Accession Day celebrations of Elizabeth I of England offered tournaments and jousting and other events performed "not only before the assembled court, in all their finery, but also before thousands of Londoners eager for a good day's entertainment. Entry for the day's events at the Tiltyard[def 6] in Whitehall was set at 12d (12 pence)".[5]

- Tournaments

References

- ↑ (2008) in Walthall, Anne: Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History. London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25443-5. pp. 4–5.

- ↑ (1984) Lives of the Indian Princes. London: Century Publishing, 210. ISBN 978-0-7126-0910-4.

- ↑ Van Zile, Judy (2001). Perspectives on Korean Dance. Middletown, CN: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6494-8. p. 36.

- ↑ Garland, Lynda (2006). Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience 800–1200. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 177–178. ISBN 978-0-7546-5737-8.

- ↑ Holbrook, Peter (1998). in Bevington, David: The Politics of the Stuart Court Masque. Cambridge University Press, 42–43. ISBN 978-0-521-59436-3.

Group Ref

- ↑ Van Zile|2001|p=69

- ↑ Walthall (2008)

- ↑ Van Zile (2001) p=6

- ↑ Van Zile (2001) p=6

- ↑ Episode 94: Sudanese Slit Drum (Transcript), https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about/transcripts/episode94/ article status: live (Publisher: BBC Radio 4/British Museum)

- ↑ McGregor, Neil (2010). A History of the World in 100 objects. London: Allen Lane, 613–. ISBN 978-1-84614-413-4.

- ↑ British Museum catalogue image of Sudanese slit drum, https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/FMgugdskR7eaWj_ST2fAeQ article status: live

- ↑ Walthall|2008

Definitions

- ↑ The emperors of the Mughal Empire, who were all members of the Timurid dynasty, ruled over the empire from its inception in 1526 to its dissolution in 1857.

- ↑ Mahārāja is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king", or "high king". A few ruled states informally called empires, including the ruler Raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, and Chandragupta Maurya.

- ↑ Nawab, also spelled Nawaab, Navaab, Navab, Nowab, Nabob, Nawaabshah, Nawabshah or Nobab, is a royal title indicating a sovereign ruler, often of a South Asian state, in many ways comparable to the western title of Prince.

- ↑ A commoner, also known as the common man, commoners, the common people or the masses, was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither royalty, nobility, nor any part of the aristocracy.

- ↑ Goryeo was a Korean state founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392.

- ↑ A tiltyard (or tilt yard or tilt-yard) was an enclosed courtyard for jousting. Tiltyards were a common feature of Tudor era castles and palaces. The Horse Guards Parade in London was formerly the tiltyard constructed by Henry VIII as an entertainment venue adjacent to Whitehall Palace; it was the site of the Accession Day tilts in the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I.

External links

Chat rooms • What links here • Copyright info • Contact information • Category:Root

![Ralph Hedley]] The Tournament (1898) Children adapting a courtly entertainment](/a/images/thumb/4/42/Ralph_Hedley_The_tournament_1898.jpg/383px-Ralph_Hedley_The_tournament_1898.jpg)