Weimar Republic

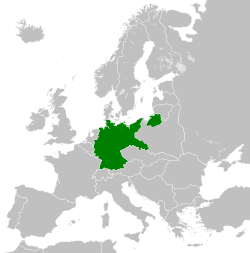

| Germany (1930) |

|

|

The Weimar Republic (German: Weimarer Republik), officially named the German Reich (Deutsches Reich), was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it was also referred to, and unofficially proclaimed itself, as the German Republic (Deutsche Republik). The state's informal name is derived from the city of Weimar, which hosted the constituent assembly that established its government. In English, the state was usually simply called "Germany", with "Weimar Republic" (a term introduced by Adolf Hitler in 1929) not commonly used until the 1930s.

Following the devastation of the First World War (1914–1918), Germany was exhausted and sued for peace in desperate circumstances. Awareness of imminent defeat sparked a revolution, the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II, formal surrender to the Allies, and the proclamation of the Weimar Republic on 9 November 1918.

In its initial years, grave problems beset the Republic, such as hyperinflation and political extremism, including political murders and two attempted seizures of power by contending paramilitaries; internationally, it suffered isolation, reduced diplomatic standing, and contentious relationships with the great powers. By 1924, a great deal of monetary and political stability was restored, and the republic enjoyed relative prosperity for the next five years; this period, sometimes known as the Golden Twenties, was characterized by significant cultural flourishing, social progress, and gradual improvement in foreign relations. Under the Locarno Treaties of 1925, Germany moved toward normalizing relations with its neighbors, recognizing most territorial changes under the Treaty of Versailles and committing to never go to war. The following year, it joined the League of Nations, which marked its reintegration into the international community. Nevertheless, especially on the political right, there remained strong and widespread resentment against the treaty and those who had signed and supported it.

The Great Depression of October 1929 severely impacted Germany's tenuous progress; high unemployment and subsequent social and political unrest led to the collapse of the coalition government. From March 1930 onwards, President Paul von Hindenburg used emergency powers to back Chancellors Heinrich Brüning, Franz von Papen and General Kurt von Schleicher. The Great Depression, exacerbated by Brüning's policy of deflation, led to a greater surge in unemployment. On 30 January 1933, Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor to head a coalition government; Hitler's far-right Nazi Party held two out of ten cabinet seats. Von Papen, as Vice-Chancellor and Hindenburg's confidant, was to serve as the éminence grise who would keep Hitler under control; these intentions badly underestimated Hitler's political abilities. By the end of March 1933, the Reichstag Fire Decree and the Enabling Act of 1933 had used the perceived state of emergency to effectively grant the new Chancellor broad power to act outside parliamentary control. Hitler promptly used these powers to thwart constitutional governance and suspend civil liberties, which brought about the swift collapse of democracy at the federal and state level and the creation of a one-party dictatorship under his leadership.

Until the end of World War II in Europe in 1945, the Nazis governed Germany under the pretense that all the extraordinary measures and laws they implemented were constitutional; notably, there was never an attempt to replace or substantially amend the Weimar constitution. Nevertheless, Hitler's seizure of power (Machtergreifung) had effectively ended the republic, replacing its constitutional framework with Führerprinzip, the principle that "the Führer's word is above all written law."

LGBT status

Weimar Germany experienced an increase in the vocalization and congregation of the LGBT community, partially due to the leniency of federal censorship. The period marked an influx in lesbian and gay media as publishers took advantage of ambiguously worded censorship laws in the Weimar Constitution. Then in 1921, the German Reichsgericht ruled that homosexual themes in press were not necessarily obscene unless erotic in nature.

Gay magazines disseminated meeting spots for members of the LGBT to gather and enabled the formation of clubs referred to as "friendship leagues." Some of these leagues would eventually integrate with the German League for Human Rights.

Weimar-era Germany also witnessed the emergence of the world’s first lesbian magazine, "Die Freundin". Although there were at least five lesbian magazines available at the time to more than one million readers across German-speaking countries, Die Freundin was the most popular. Published from 1924 to 1933, the magazine featured short stories and information about lesbian meetings and nightspots before it was ultimately shut down after the Nazis rose to power.

In 1928, the first guide to the lesbian club scene was published by Ruth Roellig entitled “Ruth Roellig’s Berlins lesbische Frauen (Berlin’s Lesbian Women).” This guide allowed women in Berlin to connect and learn more about the lesbian community.

Despite the illegality of homosexuality during this time period, references to homosexual relationships in cinema grew substantially. Two well-known films from Weimar Germany that centered around homosexual relationships are Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others), which centered around a relationship between two men, and Madchen in Uniform (Girls in Uniform), which focused on a lesbian relationship between a teacher and student. Both of these films received wonderful critical reviews and were commercial hits, opening in Berlin’s top theatres. Despite the wonderful reviews, there was still public outcry over Anders als die Andern, including riots at the cinemas where it opened, and it was even banned in various theatres, including in Munich, Vienna, and Stuttgart.

Berlin's reputation for decadence

Prostitution rose in Berlin and elsewhere in the areas of Europe left ravaged by World War I (WWI). This means of survival for desperate women, (and sometimes men) became normalized to a degree in the 1920s. During the war, venereal diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea spread at a rate that warranted government attention. Soldiers at the front (WWI) contracted these diseases from prostitutes. Hence, the German army responded by approving certain brothels that were inspected by their own medical doctors, and soldiers were rationed coupon books for sexual services at these establishments. Homosexual behavior was also documented among soldiers at the front. Soldiers returning to Berlin at the end of the War had a different attitude towards their own sexual behavior than they had a few years previously. Prostitution was frowned on by respectable Berliners, but it continued to the point of becoming entrenched in the city's underground economy and culture. First, women with no other means of support turned to the trade, then youths of both genders.

Crime in general developed in parallel with prostitution in the city, beginning as petty thefts and other crimes linked to the need to survive in the war's aftermath. Berlin eventually acquired a reputation as a hub of drug dealing (cocaine, heroin, tranquilizers) and the black market. The police identified 62 organized criminal gangs in Berlin called Ringvereine. The German public also became fascinated with reports of homicides, especially "lust murders" or Lustmord. Publishers met this demand with inexpensive criminal novels called "Krimi", which like the film noir of the era (such as the classic M), explored methods of scientific detection and psychosexual analysis.

Apart from the new tolerance for behavior that was technically still illegal and viewed by a large part of society as immoral, there were other developments in Berlin culture that shocked many visitors to the city. Thrill-seekers came to the city in search of adventure, and booksellers sold many editions of guide books to Berlin's erotic night entertainment venues. There were an estimated 500 such establishments that included a large number of homosexual venues for men and women; sometimes transvestites of one or both genders were admitted. Otherwise, there were at least 5 known establishments that were exclusively for a transvestite clientele. There were also several nudist venues. Berlin also had a museum of sexuality during the Weimar period at Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld's Institute of Sexology. These were nearly all closed when the Nazi regime became a dictatorship in 1933.

Artists in Berlin became fused with the city's underground culture as the borders between cabaret and legitimate theatre blurred. Anita Berber, a dancer and actress, became notorious throughout the city and beyond for her erotic performances (as well as her cocaine addiction and erratic behavior). She was painted by Otto Dix, and socialized in the same circles as Klaus Mann.

See also Weimar Berlin and/or Sex and the Weimar Republic

- More information is available at [ Wikipedia:Weimar_Republic ]

External links

Chat rooms • What links here • Copyright info • Contact information • Category:Root