Damsel in distress

The subject of the damsel in distress or persecuted maiden is a classic theme in world literature, art and film. She is almost inevitably a young, nubile woman, who has been placed in a dire predicament by a villain or a monster and who requires a hero to dash to her rescue. She has became a stock character of fiction, particularly of melodrama.

Some claim the popularity of the damsel of distress is perhaps in large measure because her predicaments sometimes contain hints of BDSM fantasy. The helplessness of the damsel in distress, who can be portrayed as foolish and ineffectual to the point of naïvete, along with her need for others to rescue her, has made the stereotype the target of feminist criticism.

History

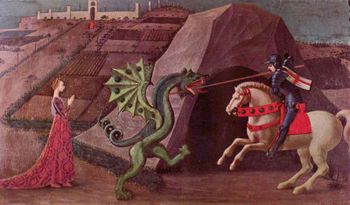

The damsel in distress goes far back into history. Greek mythology, while featuring a large retinue of competent goddesses, also has its share of helpless maidens who are sacrificed or threatened to be sacrificed. One famous example would be Andromeda, who offended Poseidon. Poseidon sent a beast to ravage the land, and Andromena's parents fastened her to a rock in the sea to appease him. The hero Perseus slew the beast, however, and thus saved Andromeda. He then married her. Andromeda's plight, chained naked to a rock, became a favorite theme of later painters. This theme of the Princess and dragon is also pursued in the myth of St George.

European fairy tales frequently features damsels in distress. Evil witches trapped Rapunzel in a tower, cursed the princess to die in Sleeping Beauty, and ensorcelled Snow White into a magical sleep. In all of these fairy tales, a valorous prince comes to the maiden's aid, saves her, and marries her.

The damsel in distress was an archetypal character of medieval romances, where typically she was rescued from imprisonment in a tower of a castle by a knight-errant. Chaucer's Clerk's Tale of the repeated trials ands bizarre torments of patient Griselda was drawn from Petrarch.

She makes her debut in the modern novel as the title character of Samuel Richardson's Clarissa (1748) where she is menaced by the wicked seducer Lovelace.

Reprising her medieval role the damsel in distress is a staple character of Gothic literature, where she is typically incarcerated in a castle or monastery and menaced by a sadistic nobleman, or members of the religious orders. Early examples in this genre include Isabella in Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, Emily in Anne Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho and Antonia in Matthew Lewis's The Monk.

The perils faced by this Gothic heroine were taken to an extreme by the Marquis de Sade in Justine, who, arguably, exposed the pornographic subtext which lay behind the damsel in distress scenario.

One of the most profound explorations of the theme of the persecuted maiden is the fate of Gretchen in Goethe's Faust. According to the philosoper Schopenhauer:

- The great Goethe has given us a distinct and visible description of this denial of the will, brought about by great misfortune and by the despair of all deliverance, in his immortal masterpiece Faust, in the story of the sufferings of Gretchen. I know of no other description in poetry. It is a perfect specimen of the second path, which leads to the denial of the will not, like the first, through the mere knowledge of the suffering of the whole world which one acquires voluntarily, but through the excessive pain felt in one’s own person. It is true that many tragedies bring their violently willing heroes ultimately to this point of complete resignation, and then the will-to-live and its phenomenon usually end at the same time. But no description known to me brings to us the essential point of that conversion so distinctly and so free from everything extraneous as the one mentioned in Faust. (The World as Will and Representation, Vol. I, §68)

The misadventures of the damsel in distress of the Gothic continued in a somewhat caricatured form in Victorian melodrama. Such melodrama influenced the silent cinema, where the damsel in distress makes a dramatic debut, tied to a railway track by a sleazy villain with trademark waxed curly moustache, in The Perils of Pauline. Sawmills were another danger faced by our heroine:

| “ | "... A bad gunslinger called Salty Sam was chasin' poor Sweet Sue "He trapped her in the old sawmill and said with an evil laugh, |

” |

Along Came Jones, by The Coasters The damsel-in-distress archetype survived well into the 20th century in the fledgling film, television, and comics industries.

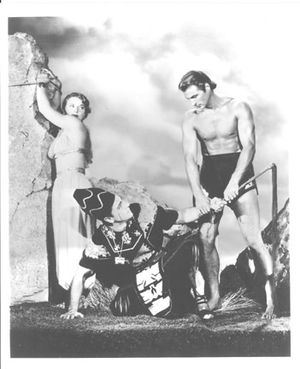

Ann Darrow from the movie King Kong is perhaps one of the more famous damsels in distress, with a giant ape capturing and holding her. Jane Porter in both the novel and movie versions of Tarzan required constant rescuing. Lois Lane is eternally getting into trouble and needs to be rescued by Superman, and Olive Oyl is in a near-constant state of kidnap to be saved by Popeye. Slightly more modern examples might include Daphne Blake from the Scooby-doo series and April O'Neil from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Today damsels in distress are not used nearly as often as they were previously, and current depictions of the stock character usually play the role as camp, although video games still feature the occasional old-style damsel. Early video games often used a kidnapped damsel in distress as the main reason for the heroes to venture out and defeat the villains. Princess Toadstool (and earlier, Pauline in Donkey Kong" video game) has required rescuing by Mario from the evil clutches of Bowser in most games of the Mario Bros. franchise. Likewise, Princess Zelda has found herself kidnapped by Ganon in the vast majority of entries in the Legend of Zelda series.

She did undergo a revival of sorts in Halloween" films, Friday the 13th, and other slasher films of the 1980s. Here, though, she was played with a twist: there were several young women characters, most of whom (often those who had been sexually active or promiscuous) were killed by the serial killer villain, but one survived to defeat him. The young woman survivor herself became a stock character, the final girl, embodied in characters such as Ellen Ripley in the Alien series. Sarah Connor, a damsel in distress in The Terminator, became the effective survivor type in Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

A Damsel in Distress is the title of a book by P. G. Wodehouse, and a motion picture that starred Fred Astaire.

Critical and Theoretical Responses

Damsels in distress are an example of differential treatment of genders in literature, film, and works of art. Feminist criticism of art, film, and literature has often examined gender-oriented characterization and plot, including the common "damsel in distress" trope.[1] Many modern writers, such as Angela Carter and Jane Yolen, have revisited classic fairy tales and "damsel in distress" stories or collected and anthologized stories and folk tales that break the "damsel in distress" pattern.[2] Often, such stories reverse the gender disparity by empowering the "damsel," or by placing boys or men in distress to be rescued by the damsel.

"Damsels in Distress

- 1 THE STALK—The Villain prepares to pounce.

- 2 THE CAPTURE—The Villain pounces.

- 3 THE RESTRAINT—The Damsel is secured.

- 3a The Gag and the Mmmpfh - (The essential ingredient for DiD purists!)

- 4 THE PERIL—The Damsel is placed in jeopardy.

- 4a The Wriggle and more Mmmpfh

- 5 THE GLOAT—The Villain teases/harasses the helpless Damsel.

- 5a The Wriggle and more Mmmpfh

- 6 THE RESCUE—The Hero arrives and defeats the Villain.

- 6a THE ESCAPE—(The Damsel somehow escapes).

- 7 THE RELEASE—The Damsel is set free.

References

- ↑ See, e.g., Alison Lurie, "Fairy Tale Liberation," The New York Review of Books, v. 15, n. 11 (Dec. 17, 1970) (germinal work in the field); Donald Haase, "Feminist Fairy-Tale Scholarship: A Critical Survey and Bibliography," Marvels & Tales: Journal of Fairy-Tale Studies v.14, n.1 (2000).

- ↑ See Jane Yolen, "This Book Is For You," Marvels & Tales, v. 14, n. 1 (2000) (essay); Yolen, Not One Damsel in Distress: World folktales for Strong Girls (anthology); Jack Zipes, Don't Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Fairy Tales in North America and England, Routledge: New York, 1986 (anthology).

Mario Praz (1970) The Romantic Agony Chapter 3: 'The Shadow of the Divine Marquis'.

See also

Chat rooms • What links here • Copyright info • Contact information • Category:Root