Little girl (comics)

In sequential art, Little Girls (capitalized and abbreviated LG in this article) are young female characters appearing in primary or secondary roles in a cartoon or comic strip. First appearing as supporting characters as early as 1895, Little Girls emerged as a clearly defined genre during the 1920s and continued to flourish over the next three decades, reaching their greatest prominence between 1952 and 1968.

At the peak of their popularity, the majority of LG characters starred in their own comic features (Li'l Jinx, Little Dot); others, such as Gloria from Harvey's Richie Rich franchise, played mainly supporting roles. Some, like Archie Comics' Little Betty, were simply child versions of better-known adult characters, created simply to exploit a trend in juvenile characters.

The genre suffered a general decline throughout the 1970s, all but disappearing by 1984 due to a widespread slump in the comics industry. Renewed interest in LG characters has occured since the 1990s, spurred on in part by the rise of the Internet and the influence of Japanese animation on Western audiences.

Early Prototypes

The use of children in popular literature and advertising was a well-established tradition by the time Richard F. Outcault drew the first episode of Hogan's Alley in 1895. Preadolescent girls in particular were noted for selling stories and merchandise, often employed as symbols of angelic purity and virtue - the popular stereotype of youthful innocence of the time.

As sequential art made the transition from single panel cartoons to weekly newstrips, it was inevitable that young female characters would make their way into the newly emerging artform. Little girls were a regular feature of Hogan's Alley, sharing equal billing with their male counterparts (at least at the beginning). Visually speaking, Outcault's girls shared many similarities with the children depicted in the popular culture of the time - except with one important difference.

Humor played a crucial role in Outcault's imagery.

Outcault broke numerous social taboos with his cartoon 'snapshots' of New York tentement waifs. Rejecting the gendered stereotypes of the late nineteenth century, Outcault portrayed underaged females as roudy, mischievous street urchins far removed from the bows and ribbons of polite New York society. This realistic depiction raised many eyebrows amongst the N.Y. World's readership, but the grass-roots comedy appealed to lower and middle-class audiences, who could relate to the strip's 'slice of life' elements.

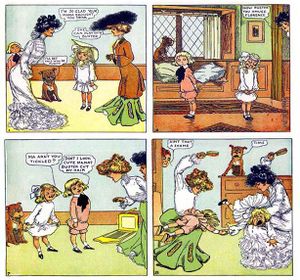

Perhaps the very first F/G comic-strip spanking occurred in Outcault's Buster Brown (October 4, 1903). As with Hogan's Alley, little girls played an important role in the Buster strip, providing the title character with suitable foils (including his sister Mary-Jane and cousin Florence). In this case, however, Outcault's rejection of existing stereotypes was considerably more subtle.

Florence, for example, appears at first glance to be a faultlessly well-behaved child, yet she is easily led astray by Buster, participating in a prank which earns her a brush-tailing over her mother's lap. In later episodes, Mary-Jane is a willing accomplice in Buster's schemes, sometimes assuming the role of a partner-in-crime and sharing the consequences of his misconduct. Despite the note of naivety pervading the characterizations, the message was clear enough: little girls could be just as naughty as young boys - even those born to wealth and privilege.

Richard F. Outcault may be credited with establishing the visual conventions commonly associated with LG characters - short skirts, elaborate footwear and oversized hairbows - but his most important legacy to the archetype was his inversion of 'normal' gendered profiling. This discreetly satirical approach transformed Little Girls from paragons of Victorian innocence into devilish bundles of mischief - a theme repeated endlessly throughout the history of the genre.

Little Girl Strips

Outcault's girls notwithstanding, the spanking of young female characters was quite rare during this period, for the simple reason that there were virtually no comic strips featuring little girls in primary roles. With a few notable exceptions - such as Windsor McCay’s The Story of Hungry Henrietta (New York Herald, 1905) or R.M. Brinkerhoff’s Little Mary Mixup (New York World, 1917) - the early comics landscape was a male-dominated terrain in which women and girls provided token support.

This disparity would be redressed during the Great Depression, when comic strips starring little girls would begin to appear. Drawing inspiration from various popular cultural sources (motion pictures and radio in particular), this new wave placed young female protagonists at the center of the narrative; a sharp contrast to the more passive characterizations of the previous generation.

Girls no longer needed a male counterpart to lead them down the garden path; they could now follow their own course of action and suffer the consequences if need be. Once again rejecting the "sugar and spice" imagery of the era, cartoonists depicted Little Girls in both positive and negative terms, making them cunning and willful on the one hand; honest and daring on the other.

Categorically speaking, LG characters of the interwar era fell into one of two main divisions. The first (and earlier) archetype was the Good Little Girl (GLG) exemplified by Little Orphan Annie (1924) or Little Annie Roonie (1927). The second, and arguably more popular model was the Naughty Little Girl (NLG) represented by Little Iodine (circa 1930), Nancy (1933) and Little Lulu (1935).

While a number of elements were common to both (generational conflict, irreverent humor), each stands in stark contrast in other respects. Good Little Girls, for example, tend to be well-behaved, self-reliant and "plucky", using their innate courage and resiliance to overcome poverty and adversity. Due to the vaguely melodramatic content, spanking imagery was rare in GLG scenarios (although exeptions were made for pathos or comic relief, as suggested by this 1924 Little Orphan Annie Sunday strip).

Naughty Little Girls, as the name suggests, were more often mischievous, accident-prone and incorrigible, spending much of their energy getting into trouble. In addition, NLGs usually came from middle class (sometimes affluent) backgrounds with stable family ties and otherwise 'normal' domestic situations. Spanking imagery featured more prominently in NLG strips, placing an emphasis on high-spirited characterization.

It was during this period (1924-1939) that many of the stylistic conventions associated with the modern Little Girl genre were established: exaggerated caricature; broad, open linework; simplified backgrounds and an emphasis on storytelling over artwork. Depression-era LG characters were frequently drawn to a specific formula, which included 'button' eyes, enlarged cranium, small mouths, slender proportions, and short skirts or dresses (this visual model was further modified during the late forties - see below).

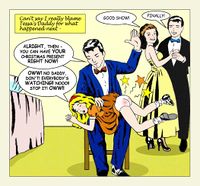

Panty-spanking was another important development of the interwar period. Due in part to their abbreviated hemlines, LG characters were often shown being spanked on the underwear - usually in the OTK position. Again, the convention was most probably introduced in the Little Iodine strip, and would be recycled incessantly throughout the next four decades. It should be noted, however, that such imagery was considered amusing by the standards of the day. Spanking in general was used for comedic effect, and rarely if ever employed the fetishistic elements common to adult depictions.

Little Girl Comics

While Lulu, Iodine and Nancy all enjoyed increasing degrees of success within the newsprint media, the Little Girl genre was still a minor player in a field overwhelmed by funny animals and male characters. The situation remained much the same throughout the remainder of the thirties, as adventure strips such as Flash Gordon, Tarzan and The Phantom began to dominate the so-called "Funny Pages."

The appearance of tabloid-sized comic books during the mid-thirties was a catalyst for change within the industry. As the decade wore on, various newspaper strips were adapted to the new medium, but somehow, most of the LG characters were left behind in the rush. The first one to make the leap was Nancy, who debuted (along with her aunt Fritzi Ritz) in Tip-Top Comics (United Feature Syndicate, 1936). Little Orphan Annie followed a year later in a short-lived series, but initially, neither garnered the kind of attention they had received in newspaper form.

Despite this apparently inauspicious beginning, Little Girl characters continued to gain popularity during the 1940s, eventually outstripping the competition by the middle of the 50s. The reasons for this can be traced back to a single event in 1943: the release of Little Lulu's first animated cartoon, Eggs Don't Bounce.

Lulu was licenced by Famous Studios between 1943 and 1947, appearing in a total of 25 theatrical shorts. Her adaption into animated form made Lulu an instant star and demonstrated the sales potential of Little Girl characters to comic book publishers. Within a few years, related merchandise was flooding the market; Little Lulu was being featured in everything from magazine advertisements to paper dolls and lunchboxes. And quite suddenly, Naughty Little Girls were the "next big thing" in the comics industry. Dell Comics started publishing Marge's little Lulu from 1945, where the character enjoyed her greastest success.

Spanking scenes occurred in at least two of the Little Lulu cartoons (Lucky Lulu, 1944 and Bored of Education, 1946), although Lulu wasn't the only recipient (that particular honor was shared with her long-time nemesis, Tubby Tomkins). Spanking took place at more regular intervals in the comic book. Drawn by veteran artist John Stanley, Lulu's spankings were largely slapstick affairs, most often the result of a domestic dispute with one of her parents (usually her father). In accordance with the precedents set during the 1930s, Lulu was spanked over the knee and on the underpants; a practice probably considered the norm at the time - in comics if not in real life.

Little Audrey

The LG genre received a second boost in 1947, when Famous Studios released Santa's Surprise, marking the animated debut of Little Audrey. As noted by several comics historians, Audrey was created as a replacement for Little Lulu after Famous failed to renew the character's licence. The reasons why the company decided to drop the highly successful Lulu series are unknown, but evidentally, the concept itself was considered worth pursuing. Audrey's first starring role was Butterscotch and Soda (1948), launching a series which would last until 1959's Dawg Gawn.

1948 saw Audrey's adaption into comic book form. Initially licenced by St John Publications, Audrey starred in 24 issues of her own title (1948-1950) along with a yearbook and some incidental merchandising. A short-lived newstrip was then published by King Features Syndicate from 1950-1951. The character's success generated new interest in Little Girl strips in general.

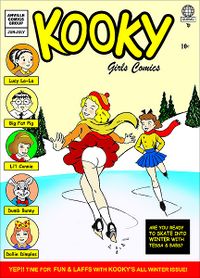

A veritable legion of titles sprung up virtually overnight. Archie Comics' Li'l Jinx appeared the same year as Santa's Surprise (1947), becoming that company's premier LG title. Harvey introduced Little Dot in 1949, paving the way for an entire dynasty of child-friendly characters. Marvel's short-lived stab at the genre included Little Lizzie (1949), Little Aspirin (1949) and Little Lana (1949). More soon followed as publishers began to recognise the potential of the Little Girl market.

In the meantime, the Audrey franchise continued to grow.

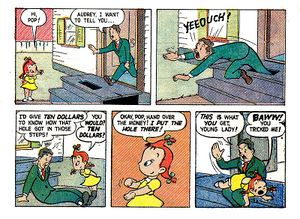

St John's Little Audrey emulated both the visual style and slapstick approach of the animated version. On closer comparison, however, one significant difference becomes apparent. Unlike the cartoon series, the comic strip featured regular spanking scenes, as implied by the image reproduced at right.

Following the conventions of the previous decade, the spankings scenarios were laced with domestic humor, normally the result of an innocent mistake on Audrey's part. As always, generational conflict played a major role in proceedings, with discipline being provided via parental hand. This stood in stark contrast to the theatrical shorts, where Audrey's mischief invariably went unpunished.

Harvey Girls

By 1951, Little Audrey was appearing in three separate venues (comics, cartoons and newstrips), making her perhaps the most easily recognised LG of the early fifties. As noted above, Audrey was never as successful as Lulu, Iodine or Nancy; nevertheless, it should be remembered that she was the only female character to appear in her own animated features during the 1950s. In addition, Audrey's comic strip incarnation was popular enough to inspire a new generation of children's strips, providing a model which would last out the next two decades.

The process began in 1952, when Little Audrey (along with several other Famous properties including Casper the Friendly Ghost) was licenced to Harvey Comics. As with the St. John character, Harvey's version followed the animated design very closely, essentially transferring Famous Studio's house style to the comics medium. It was in this venue that Audrey was to achieve her greatest success, becoming an archetype whose influence would persist until the present day.

According to comics historian Don Markstein, Harvey redesigned a number of its features during the early fifties. This was almost certainly done to bring them more in line with the newly licenced properties. Suddenly, all of Harvey's headliners began to resemble Casper and Audrey. This was particularly evident with Vic Herman's Little Dot, who took on proportions and characteristics practically identical to Little Audrey's.

Audrey's impact was felt across the board; from 1953 onwards, the majority of Harvey's LG characters were given the 'Famous' treatment, even those only cast in supporting roles: Pearl (From Spooky), Gloria (from Richie Rich), and Wendy the Good Little Witch (from Casper; later star of her own title) being some of the more obvious examples. Even the morbidly obese Little Lotta shared some visual affinities with the Audrey template.

Classic Era

Harvey was arguably the most successful publisher of Little Girl comics during the 1950s, if only by virtue of numbers: throughout the decade, Harvey published no less than five female characters under their own titles. The company was not without its rivals, however.

Harvey's chief competitor during this phase was Dell, generally considered the most successful comics publisher of the Golden Age. In addition to reprinting the adventures of Iodine, Lulu and Nancy, Dell also featured Mary Jane & Sniffles in the back pages of its best selling Looney Tunes book. Starting out playing second fiddle to Sniffles the Mouse in 1941, Mary Jane became the strip's headliner during the fifties - possibly in reaction to the rising popularity of LG characters. Beautifully illustrated by Al Hubbard, the series combined three seperate genres (funny animal, little girl and magic) to create one of the most original children's fantasies of the day.

Joe Edwards' Li'l Jinx was an exact contemporary of Little Audrey, taking her bow in 1947. Published in various forms by Archie Comics from the late forties to the mid-seventies, the strip revolved around the often exasperating relationship between a wisecracking child and her long-suffering father. Like most of Archie's output of the time, the stories were well-written and genuinely funny, offering some clever insights into family life. Despite Jinx's frequent misconduct, spanking scenes were surprisingly rare - Hap Holiday tended to view his daughter's antics more with a rueful smile than anything else.

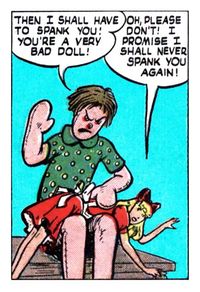

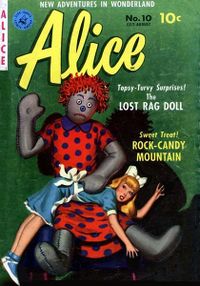

Ziff-Davis leapt onto the LG bandwagon in 1951, with two fantasy-based strips; Alice: New Adventures in Wonderland and Dolly: Wonderful Adventures in Toyland. In point of fact, Lewis Carroll's Alice is one of the most successful fictional girls in history, having been adopted into comics, animation and live-action venues more than any other LG character (closely followed by Little Red Riding Hood and Goldilocks). Both titles reflect the almost universal association of little girls with fairy tales and magic in the popular consciousness.

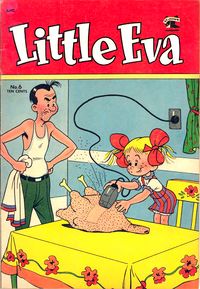

The final entry into the field was St John's resident Audrey clone, Little Eva. Making her debut in 1952, Eva became St John's starring attraction after the Little Audrey licence passed on to Harvey. Employing the same artists and writers, Little Eva continued the slapstick tradition established by her predecessor. While not in the same league as its rivals, the strip continued into the early sixties, published first by St John, then by Pines Publications. Interestingly, Little Eva was even translated into French under the name "Rosette" - at a time when strict limitations were imposed on the number of American comics available in Europe.

The Comics Code

One of the most significant events in the history of post-war comics was the establishing of the Comics Code Authority in 1954. While the details surrounding the Code's advent are too complex to discuss here, a brief outline is necessary to explain its effects on the comics industry, particularly the LG genre.

Briefly speaking, comics had come under under intense public scrutiny during the late forties, due in large part to the accumulation of crime, horror and 'good-girl' titles that had flooded the newstands towards the end of the decade. Psychiatrist Fredrick Wertham had identified comics as a corrupting influence on America's youth and had mounted a campaign against the sale of such material to young children. Wertham's crusade eventually led to a congressional inquiry into juvenile delinquency.

One of the outcomes of the senate subcommitte hearings was the formation of The Comics Magazine Association of America, a coalition of mid 50s publishers which included DC, Atlas (Marvel), Harvey, Archie, and - initially - EC. Seeking to counteract the extreme public reaction to Wertham's anti-comics crusade, the CMAA instituted a universal editorial policy meant to restrict the visceral content of comic books and related media.

While stopping short of outright censorship, the Comics Code was tremendously influential during its first two decades, purging the industry of visual material deemed anti-social or undesirable. Much of the Code's wording was meant to remove all sexual references from the medium, along with extreme violence and bloodshed. Similarly, supernatural elements had to be toned down if not deleted entirely.

Combined with rapidly falling sales across the industry, the Comics Code sounded the death knell for hundreds of titles. Many smaller publishers were driven out of business. Larger operations - such as DC and Atlas - attempted to tailor their product to the Code's restrictions with various degrees of success. Ironically, the companies which handled the more child-oriented material actually thrived in the new climate.

Dell Comics, who dealt mainly in funny animals, emerged virtually unscathed from the controversy. Harvey, which had published some of the goriest horror comics in the business, simply refocused their efforts on their children's line - a move which proved surprisingly lucretive. St John, which licenced numerous cartoon and newstrip characters, continued publishing kid-friendly series throughout the fifties.

In a sense, the Comics Code provided a substantial boost for the young children's market, and by extension, for the Little Girl genre. While the rest of the industry suffered a mass extinction, characters such as Little Audrey and Wendy the Good Little Witch became far more viable than ever before. Little Girl strips were considered cute, wholesome and entirely appropriate for their juvenile audience (at least when compared to Crimes By Women or The Crypt of Terror).

Strangely, although the Code had banned sex, violence and horror from the comics landscape, no reference whatsoever was made to any form of corporal imagery. Presumably this was because the spanking of children (and adult females) was perfectly acceptable to the Code's architects.

Notable LG Strips

Notable "Little Girl" Strips

Links

- Don Markstein's Toonopedia

- Harvey Entertainment

- Harvey Comics (Wikipedia)

- Handprints Comics Gallery

- Shoujo Imageboard: Toongirls

- Shoujo Imageboard: Downloads